27th JAMCO Online International Symposium

December 2018 - March 2019

The Future of Television: Japan and Europe

The Future of TV: Back to basics, leveraging its strengths

Few would dispute that TV was the king of media from the latter half of the 1960s through the 2000s. TV far surpassed the three other advertising media both in terms of funding and in its impact on viewers and advertisers. It was also believed to be of benefit to the public and is still a major presence.

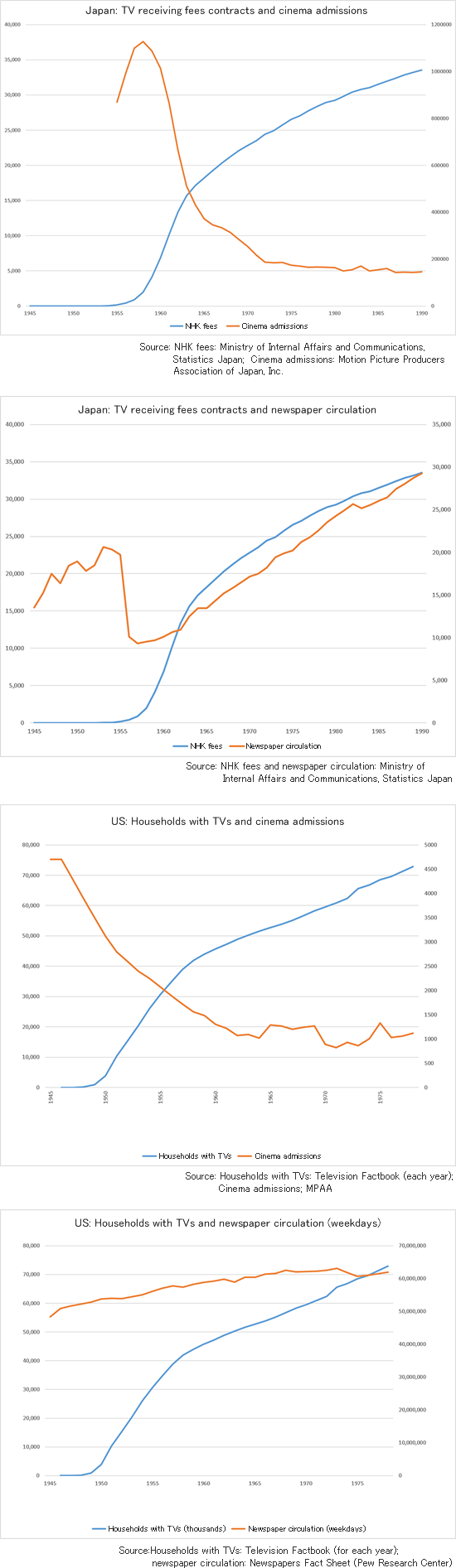

The figure below shows newspaper circulation, cinema admissions, and TV uptake in Japan and the US in the 20th century. TV arguably became as entertaining as the cinema, resulting in its rise. However, it was not strong enough to take on the journalistic power of newspapers. I believe the opposite paths taken by cinema and the press offer many pointers with respect to the outlook for the competitive relationship between online media and other media. In this paper, I consider TV in the 2020s—when the internet will likely secure its position as a full-fledged video medium—in light of past developments.

Figure 1

2. The internet and the four traditional media

The internet evolved from simply being a transmission channel for private telecommunications, such as email, and started to have value as a medium suited to targeting the general public. When Windows 98 superseded Windows 95, PCs that ran word processing and spreadsheet software (typically like MS Word and Excel) proliferated among ordinary users, the World Wide Web expanded, centered on text and images, and people started to become aware of broadband networks, such as ADSL.

Book sales peaked in 1996–99, magazine sales in 1996–98.1) Newspaper circulation peaked in 1997–99, then went into decline. 2) Proving a causal relationship between these developments and the internet looks easy but in practice is not. However, the web definitely met demand for the printed word in some way.

People may now be distanced from physical media such as paper-based media. Nevertheless, the “text” continues to be distributed, including via the web, satisfying demand of people. Publishers’ and newspapers’ sales of paper-based media also continue to decline and the B2C business space has contracted. However, in B2B business, the provision of news stories and copy by newspapers, telecommunications companies, and magazines to websites that distribute news has increased. Major operators of news sites are not primary news gatherers or journalists. Will website operators expand from the news gathering and compilation domain to the reporting space? From this perspective, it is worth focusing on the management decisions taken by Cyber Agent with an eye on its AbemaTV joint venture business, which is using the ANN reporting network in cooperation with the company.

Illegal streaming of music via the internet started to be viewed as a problem in the Windows 2000 era, in other words, around the year 2000. This was also when ADSL and other optical fiber networks became known and proliferated among the public. It was then that internet speeds made the transmission not just of text and images but also of music data realistic. Around then, large-scale illegal streaming became possible thanks to P2P sharing software such as Napster (1999–), Share (2004–), and Winny (2002–). On the other hand, legitimate digital music data distribution services also launched, including Chaku-uta (2002–), Chaku-uta Full (2004–), and iTunes Music Store (2004–). However, there was resistance to pay as you go billing, as it was felt to be out of character with the internet and to hinder the convenience implied by the phrase “anytime, anywhere” (pay as you go uptake was very slow, as fixed rate plans for mobile phone usage and freemium models for streaming services such as Spotify became entrenched).

In Japan, music sales, including music CD sales, peaked at around ¥607.5bn in 1998 and have been declining ever since. This would have been largely attributed to illegal music streaming. According to one view, pirated music on the internet is easy to obtain and of sufficient quality to depress legitimate CD sales, and this has eroded legal sales. Another view is that content obtained for free likely has a promotional impact for the artist, regardless of whether the music is obtained legally or illegally. Regardless, CD sales continued to decline, data at one point indicating that the younger generation was becoming estranged not just from CDs but perhaps from music altogether.3) Fortunately, a reversal can be observed in recent data. We are starting to see a different style of music enjoyment from that when CDs were at the height of their popularity. In other words, the flow of (pop culture-related) music penetration has changed. In the past, various kinds of advance promotion were implemented, which was ultimately reflected in CD sales. This included TV programs that featured songs and concerts. However, in recent years, so-called “festival concerts” have become popular in the music business. Various kinds of promotion are carried out in advance of these concerts to maximize ticket and merchandise sales and, ultimately, excitement at the concert. CD sales and distribution of promotional videos via the internet can be viewed as part of this. In short, we should say that the business model has changed, and the music business has adapted to the internet age.

After text, images, and music, the next type of content to be distributed via the internet was video. YouTube launched in December 2005 and Netflix started to migrate from a physical disc rental business to internet streaming in January 2007. At that time, the uptake of mobile devices such as iPhones was greater than that of PCs (the iPhone was launched in 2007). These are devices that strengthen the idea of “anywhere” in addition to the internet on PCs, which were tied to the home and the office. At first there was some doubt about displaying video on a 5-inch screen, but it gradually took off, even in Japan, where it centered on the distribution of anime content. In the US and Europe, distribution business aimed at smart TVs connected to the internet, as well as at smartphones, proliferated rapidly due to the efforts of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and the like. The rental video business, which had long had a poor reputation for the levels of service provided, and cable received a direct hit (so-called cord cutting), the former in particular being virtually wiped out in North America.

The illegal distribution of video is also a serious problem, but including the steps taken to counter it, anime, which is a business initially developed in Japan, has evolved into a genre likely to develop globally (thanks to the internet), and producers are seeking new forms of window control, including with TV and the internet.

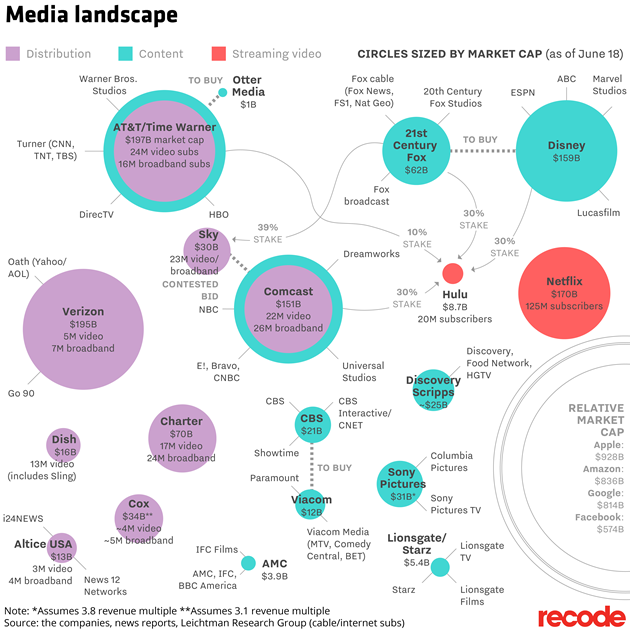

One of the special features of the IT business is its strong fundraising capability. Many companies in the segment have histories of becoming major companies over a short time frame from their beginnings as start-ups. They excel at growing large while maintaining high turnovers of funds. At some point, IT companies came to dominate today’s US and global rankings (measured according to market value, for example). In the 2010s, video streamers Netflix and Amazon also became part of GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon) and FANNG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, NVIDIA, and Google), and the public became aware of them as major companies. Existing media companies have been forced to beef up their management decisions both in terms of competition in content (programs and content) and in their ability to compete for funds and in competitive relationships (acquisitions, etc.) The Disney/Fox merger probably also makes sense if one interprets it in this context. The merged company will be on a par with companies like AT&T/Time Warner, Verizon, Comcast, and Netflix. It will finally surpass Netflix which is a member of FANNG.

Figure 2: US media companies ranked by market cap

Source “Here’s who owns everything in Big Media today”, https://www.recode.net/2018/1/23/16905844/media-landscape-verizon-amazon-comcast-disney-fox-relationships-chart

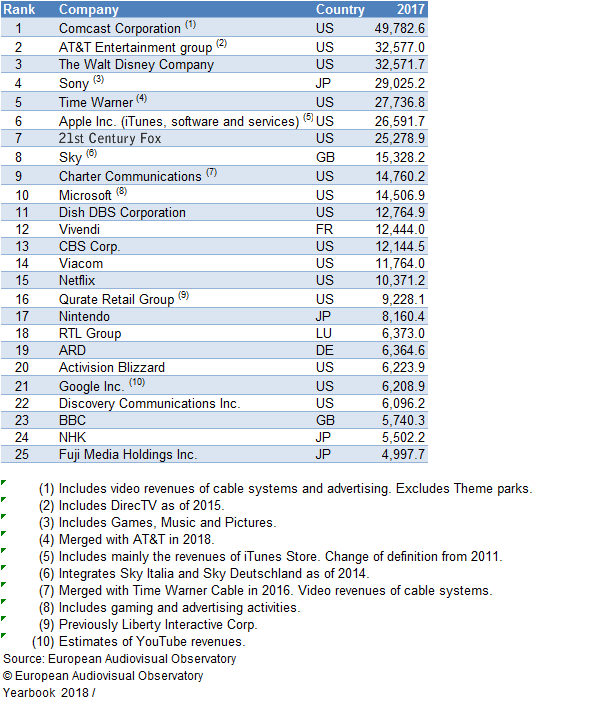

Figure 3: Global media companies ranked by sales

(EUR million)

3. Grounded in the concept of ubiquity, TV beat cinema, and now the internet is challenging the four mass media

The idea that the internet should be ubiquitous has been part of the concept since it first came into being. In fact, considering the competitiveness of a medium, ubiquity is to quite a large extent part of its nature. For example, film lovers had to overcome many obstacles before they could enjoy movies at a cinema. They had to find out that the movie existed, be interested in it, check the screening times, fit seeing it into their schedules, travel to the cinema, pay for a ticket, and so on. This is the archetypal AIDMA (Attention, Interest, Desire, Memory, Action) model of marketing. TV reduced the number of steps. TV could entertain via some kind of program “at any time and at home.” Home video, which started to proliferate in the 1980s, ushered in on-demand viewing at home, strengthening the “anytime” function. “Ubiquitous” is widely understood to mean “anytime, anywhere”, and the spread of mobile internet devices (not PCs) obviously released users from the limitation of “you have to be at home,” which had remained with TV.

With the internet, designers considering viewer flow often ask how many clicks (operations) it will take to get to the target information, testifying to the degree of consideration given to ergonomics and user-friendliness.

4. The film industry’s predicament in the 50s through the 70s and how it responded

The blockbuster strategy supported the film industry for around 30 years, from the mid-70s to the mid-2000s. Before then, the following were observed not only in Japan, but worldwide:

1950s: substantial decline in cinema admissions, studio system starts to collapse,

1960s: major movie companies struggle (takeovers, bankruptcies), independents relatively active,

1970s: blockbuster strategy in the era of TV, cable, and home video.

In the 1950s, attempts were made to attract people away from TV using technology and multimedia, including trials of TV-like services in cinemas (theater television), 3D cinema, and smell-o-vision (4DX service today). In the 1960s, under the banner of “diversity,” companies that were relatively independent from the majors were active (e.g., the avant-garde works of the French New Wave or Nouvelle Vague era). However, this was a niche market and it represented an evolution towards it becoming more difficult to support film making, which takes considerable time and effort and is very costly. Despite these developments, the traditional business model of showing films in cinemas managed to survive into the 1970s, but the films were mostly highly commercial blockbusters that capitalized on the differences between cinema and TV/home video (the characteristics of the medium, large screens, high image quality).

It would not have been surprising if the cinema business had been extinguished by the emergence and swift spread of TV. As with the internet today, TV at the time was innovative and evolved very rapidly, and people were mesmerized. Film contracted sharply, as noted at the beginning of this paper, and some majors in all countries went bankrupt. Shorts, news, and various other genres disappeared from theaters, shifting to TV. However, film did not disappear. It is also true that filmmakers continued to yearn to make movies during the 20th century, when the phrase “they’ll turn it into movie some time” was often heard. Movies took longer and were much more expensive to make than TV programs, but, conversely, they also reflected the care taken in making them and were a highly expressive medium for both producers and consumers (an easy-to-understand example is shown in differences between movies and TV in terms of moral systems and the checking and regulation of content). Even though all kinds of new media have emerged since TV, they have come to be positioned as part of fundraising to maintain movie-like production, with window control and window strategies being established. Although the hugely powerful medium of TV proliferated during the 20th century, there was also an intense desire to protect the movie theater business of film industry themselves.

5. Broadcasting: the core must be defended

The broadcast of 4k content via satellite (BS4K) began in Japan on 1 December 2018. Looking at all the companies’ offerings, services started with new channels that differed from existing 2k broadcasts via satellite (2KBS).

Looking back, public expectations of the existing broadcasting industry have remained high in parallel with the rapid development of the internet since the 1990s. Before satellite broadcasting began, commercial broadcasters mostly engaged in terrestrial broadcasting. Subsequently, when society became aware of a new technology, such as satellite (BS, CS), multiplex, teletext, and data broadcasting and catch up services, major broadcasters, especially the key Tokyo-based broadcasters, felt pressure and expectations to participate in some way. Today (2018–19), in addition to the 4k satellite broadcasting mentioned above, the majors are expected to start up the simultaneous transmission of terrestrial broadcasts via the internet. The public still has great expectations of the broadcasting industry.

Can the industry meet them? It is thought that all broadcasters will not be able to meet all the demands. Most commercial broadcasters (especially local companies) do not compete as fiercely for investment as the IT industry, as mentioned above, and there are concerns about whether these new businesses will justify the investment. It would be good if the public’s expectations guaranteed a little profit, if not major profits, for private-sector companies. However, usually, the public is only interested in how it can benefit and shows no interest in paying for it. As the number of options increases, we are now in an era in which managers must think about “consolidation.” Most broadcasters differ somewhat in terms of size compared with the giant corporations, mostly manufacturers, that make up the Nikkei 225 index.4) They do not possess the kind of resources major manufacturers do, which is another reason why it is thought that meeting all public expectations will be challenging. As noted above, US mega-media and the Hollywood majors are also in terms of corporate power (market capitalization from today’s perspective) prepared to compete with the developing IT industry, but it is hard to imagine the same development in other countries, including Japan.

Naturally, therefore, differences arise in terms of management focus, some broadcasters focusing on high quality, such as 4k broadcasts, some on programs and content that includes planned content, and some on internet business that increases viewer convenience. For example, Hokkaido Television Broadcasting has for many years developed local creative resources and content typified by the sale of programs overseas and a program called “Suiyou Dou Deshyou?” (How do you like Wednesday?) (as has Television Shin-Hiroshima System (TSS)). In recent years, the Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN) has been working hard on 4k and 8k broadcasts and on in-house program production. Many broadcasting companies, especially Osaka-based ones, interested in how to leverage the internet, are participating in The Multiscreen Broadcasting Study Group, popularly known as Tsushomaru.5)

I believe it is right that the differences between each company should become so large, but whichever option they select, they will have two things in common. One is continuing to create images (rather than TV programs). Also, regarding their business portfolios, they must continue to rely on existing broadcasting revenues for their core revenues (in Japan, business activities via terrestrial broadcasting) for at least ten years and they must put this mainstay on a firm basis. Fortunately, advertisers and viewers in Japan are lagging slightly behind Europe and the US in terms of shifting from TV to the internet. Deciding which of the strategic options outlined above to adopt with broadcasting business at the core while making clear what kind of contribution to make to improving broadcasting business (for viewers) is logical based on classical business diversification theory.6)

6. A blockbuster strategy for broadcasters

The film industry regained a kind of vigor that differed from that of TV in the 70s, recovering from its slump, due to high-concept blockbusters starting to be successful. The headliners were Jaws, Star Wars, The Godfather, and The Exorcist. Similarly, in competition with the internet, I believe that concentrating on genres, programs, and other content that is difficult for internet companies to make will be effective for broadcasters.

From another perspective, when movies competed with TV, only blockbusters survived in theaters, while other genres were stolen by TV. Virtually all other genres—shorts, news, documentaries—were taken by TV because this suited viewers and program suppliers.

Is something similar happening with TV now? Music programs have vanished from all broadcasters. TV Asahi’s music station slot is about the only network music program left. As for broadcasting slots for movies, previously each broadcaster had one or more slots per week, but today, the only network program is NTV’s Friday Roadshow. It is also true that, with a few exceptions, anime has vanished from weekday prime time slots on network TV. The Broadcasting Act stipulates that broadcasters must put together a comprehensive range of programming. However, with many kinds of media and a changing environment, the range of genres the public expects among broadcast programs is gradually narrowing. Movies, music, and animation have not disappeared. It is just that demand for these genres is being satisfied via means other than broadcasting.

Netflix and Amazon, as part of their expansion strategy, initially made all kinds of acquisitions and secured content to expand their product lineups. However, it appears that this phase is now over. That neither made any acquisitions at the 2018 Sundance Festival7) was a talking point. It was pointed to as an effort to corral production companies and creators who make original content, as part of the trend to expand original content that started a few years ago. The nature of competition is shifting from expanding content lineups to securing development of killer content.

Given the different competitive attributes of movies and video streaming services, broadcasters should “consolidate” and should have the genres, programs, and content to win. The key Tokyo-based broadcasters, Japan’s main broadcasters, and local broadcasters should each have their own perspectives. For example, Netflix and Amazon concentrating film and TV production in one prefecture may be easier from a resources volume perspective, but in many ways does not match the global scale of their business, and they do not have motivation to engage enthusiastically in production. Regarding the production of Japanese content, in competition between the key Tokyo-based and second-tier broadcasters and global capital, the key Tokyo-based and second-tier broadcasters should have an advantage as a result of having cornered influential Japanese people and creators resident in Japan due to having done business there for many years and being intimately familiar with the details of the industry.

Nevertheless, there is no sign of a compartmentalization into the global players, domestic majors, and regional players of the internet era. However, what is being pointed out in various situations now, too, is differentiation in terms of the reliability of the information provided. Internet content by nature has issues in terms of reviewing and examination and is said to have differentiation attributes the four traditional media should pursue.

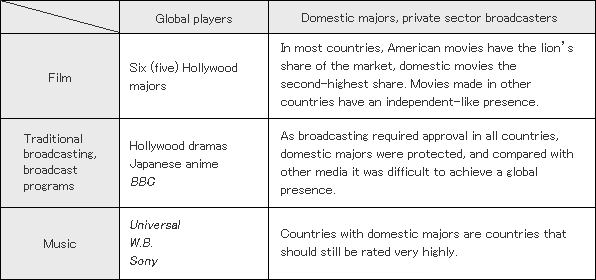

7.Global competition comes to domestic broadcasting system

The presence of global players like Netflix and Amazon will at least result in direct competition with the rental video business in all countries, and if they grow larger, they will compete with film and TV business. Because broadcasting was a licensed business worldwide, historically it was difficult for companies to grow into global players. It was also a business with a strong domestic perspective in all countries, so, only domestic majors formed. At most, there was just, via the sale of programs overseas, Hollywood dramas, Japanese animation, news and documentary exchanges via broadcasting federations around the world acting as nodes, and small-scale overseas broadcasting for expats. Looking ahead, we should expect global players to exhibit a presence in competition.

Figure 4

Using these global players will be an option in the development of programs and film and TV overseas. The fact that some broadcasters are already, in partnership with these global players, producing programs for terrestrial broadcasting and streaming businesses, and have started product development exceeding their own broadcasting areas and multi-use of programs, looks highly promising for those viewing this from outside, as it suggests business expansion.

Notes

- All Japan Magazine and Book Publisher’s and Editor’s Association (AJPEA) “Japan Publication Statistics” https://www.ajpea.or.jp/statistics/

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications “Japan’s Long-term Statistics” https://www.stat.go.jp/data/chouki/26.html

[Materials] The Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association “Japan Newspaper Annual” (periodical) - Recording Industry Association of Japan, annual “Survey of Music Media Users.”

- Regarding related areas, Japan’s Big Three telecommunications carriers are constituent stocks, as are Toho in the film industry, Dentsu among ad agencies, and Cyber Agent in IT, but no companies considered to be broadcasters by the public are included.

- https://multiscreentv.jp/index.html 91 corporate members (including 62 broadcasters) as of August 31, 2018.

- For example, focus on mainstay business, diversification of ancillary business identified by Rumelt. Rumelt, R. P.,(1974),Strategy, Structure and Economic Performance, Harvard Business School, 1974.

- https://www.businessinsider.com/sundance-2018-amazon-netflix-buys-2018-2018-1

*Links are for posted items. It is possible that some items are not currently available or are being edited.

Takashi Uchiyama

Professor of policy studies, Graduate School of Cultural and Creative Studies,

Aoyama Gakuin University.

t2uchiya@sccs.aoyama.ac.jp

Specializes in film and television content industry management strategy and government economic policy.

1994: Completed the second half of the curriculum for a doctorate in management studies at Gakushuuin University graduate school. Left the university.

Researcher, the Japan Commercial Broadcasters Association Research Institute, special senior researcher, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP), etc.

Return to 27th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 27th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page