23rd JAMCO Online International Symposium

February 2015 - October2015

Audience Perception of Japanese TV Programs in Asia and the Middle East.

Possibilities and Issues in the Secondary Use of Japanese Educational Video Programs in Developing Countries:

Jordan, Uzbekistan and the Philippines

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine the possibilities and issues in the use of educational video programs produced for Japanese viewers in supporting the education of students in developing countries. So far, the possibilities of using educational video programs produced in Japan to support classes in developing countries have been under discussion (i.e. Kodaira, 1994, and Ichikawa, 1990). Therefore, in this paper, we will study how Japanese educational video programs are understood and interpreted in classrooms in developing countries.

1. Research Background

2. Research Objective

In order to reveal the possibilities and issues in the secondary use of Japanese educational video programs in developing countries, this study aims to examine whether science education programs, translated by JAMCO but minimally influenced by cultural differences, can be extended to and used in educational settings in developing countries.

The target countries are Jordan (Amman), Uzbekistan (Tashkent) and the Philippines (Bulacan). The reasons why these countries were selected are stated in 3.3.

3. Research Summary

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to investigate how educational video programs owned by JAMCO are understood and interpreted in developing countries, in order to clarify the possibilities and issues regarding the secondary use of Japanese educational video programs in these countries. Studies were conducted in August 2014 in Jordan, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines.

Research results showed that, despite requests to have the programs translated into local languages, they can be used satisfactorily in English as classroom material. Several issues in the designing of coursework were clarified through the research, such as how teachers with no experience in using educational video programs should incorporate them into class, what kind of questions the teachers should ask as the students watch the programs, and when to make time for students to think things over.

Although Kodaira (1994) proposed preparing textbooks for teachers, incorporating educational video programs into classroom education means that the entire coursework structure is bound to change. Simply handing over such video programs as classroom material may prevent teachers from fully appreciating the significance of such material and making use of it. Therefore, training in designing coursework should be provided when the programs are provided. In other words, when we provide the programs, we will need a system that also provides opportunities for workshop training in using educational video programs in class, as well as seminars where teachers can sit in classes using educational video programs and discuss the contents of the coursework among themselves.

Reference

*Links are for posted items. It is possible that some items are not currently available or are being edited.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the possibilities and issues in the use of educational video programs produced for Japanese viewers in supporting the education of students in developing countries. So far, the possibilities of using educational video programs produced in Japan to support classes in developing countries have been under discussion (i.e. Kodaira, 1994, and Ichikawa, 1990). Therefore, in this paper, we will study how Japanese educational video programs are understood and interpreted in classrooms in developing countries.

1. Research Background

- 1.1. History of the use of educational video

programs

The expansion and development of school broadcasting in Japan has been largely due to the use of nation-wide broadcast material under the guidance of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (hereinafter referred to as MEXT) with regional boards of education and the efforts by Zenporen, a voluntary research organization of school-teachers which takes place various workshops hosted by the teachers themselves (Ichikawa, 1990). Some countries have the capability to work on expanding and developing educational broadcasting on their own, like Japan, while other countries lack information and telecommunications infrastructures or know-how in educational broadcasting.

One of the most widely broadcast educational video programs around the world is “Sesame Street”, which was produced in the United States. The program was born out of a need to enhance preschool education, and has been broadcast in over 130 countries in various forms. According to Cole (2007), when a new country or region is selected to broadcast “Sesame Street”, the program is produced by the people in the country or region. Therefore, it has been reported that video programs can be produced to suit the educational needs of the students in that country or region. In other words, the varying educational approaches and backgrounds for each country are taken into account during production.

As a result, a number of diverse projects have been started to achieve various educational goals around the world. Examples include projects aimed at acquiring cognitive skills such as elementary mathematics, problem solving, and reading and writing, and projects aimed at acquiring social skills, such as social interaction and studies about family and neighbors.

One thing to keep in mind, however, is that “Sesame Street” has been produced to suit the educational approaches and backgrounds of the countries where it broadcast. As educational materials, methods, and video programs are connected closely to the time and place in which they originate, it has been pointed out that the educational context, when separated from a particular situation and applied elsewhere, may be altered (Yamada, 2009). In other words, when a video program produced in one country is applied to another, the issue of cultural differences may become apparent. - 1.2. Expectations of developing countries for educational

video programs produced in other countries

Based on the abovementioned issues, let us examine how educational programs now in Japan can be applied to other countries.

The Japan Media Communication Center (hereafter referred to as JAMCO) translates educational video programs produced in Japan into English, Spanish, and French. The programs are then transmitted abroad. The purpose of this undertaking is to provide assistance in improving the quality of education and to provide information on Japanese culture. This is in line with the movement promoted by MEXT and other government institutions (MEXT, 2013).

However, as mentioned, video programs produced in one country – Japan – may present cultural differences when extended to educational settings in other countries. Therefore, when Japanese educational video programs are aired overseas, their subject, chapter, and program content must be selected considering the cultural situation of the target country.

2. Research Objective

In order to reveal the possibilities and issues in the secondary use of Japanese educational video programs in developing countries, this study aims to examine whether science education programs, translated by JAMCO but minimally influenced by cultural differences, can be extended to and used in educational settings in developing countries.

The target countries are Jordan (Amman), Uzbekistan (Tashkent) and the Philippines (Bulacan). The reasons why these countries were selected are stated in 3.3.

3. Research Summary

- 3.1. Selection of educational video programs

The authors made trips to Jordan (Amman), Uzbekistan (Tashkent) and the Philippines (Bulacan) in August, 2014, and conducted studies by asking local educators to view educational video programs that had been translated into English with the cooperation of JAMCO.

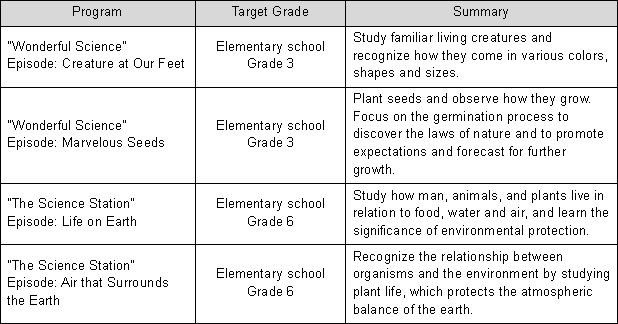

Based on Kodaira (1994), we selected 4 educational video programs for viewing in each of the three countries (Chart 1). The programs were “science” video programs, which are minimally influenced by cultural differences, and show how experiments concerning natural science are conducted.

Chart 1: Selected Programs

- 3.2. Research method

Selected science educational programs were viewed by teachers and students, followed by semi-structured interviews. We referred to Kodaira (1994) for these interviews, which include the following questions.

– Questionnaire items for teachers

- (1) Did you find the contents of the science programs suited to your lesson contents?

- (2) Do you think that the format of the programs enables you to utilize them in your own class?

- (3) Have you ever viewed a science video program? Have you ever used one in class?

- (4) What should be done to enable the effective use of these video programs in your country?

– Questionnaire items for students

- (1) What was the video program about? (Understanding)

- (2) Was the video program interesting? What was interesting about it? (Interest)

- (3) Was the video program content too difficult for you? Which part did you find difficult? (Understanding)

- (4) Did you understand the experiments? Do you want to conduct experiments on your own? (Interest in experiments)

- (5) Would you like to see more video programs like the one you just saw? Can you tell us why? (Viewing eagerness)

- 3.3. Summary of target countries

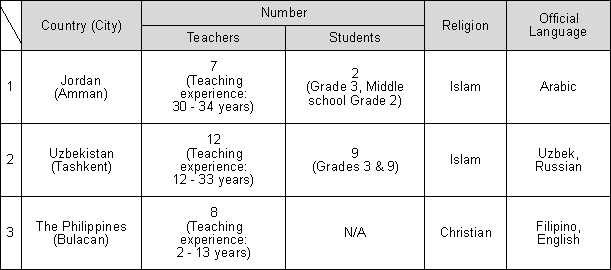

The study targets were selected for the following reasons: 1) Electricity is available on a daily basis in school settings, enabling the use of educational video programs in class, and 2) English is studied as a primary or secondary language (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Research Targets

Jordan

In Jordan (Amman), the study was conducted at a school for Palestinian refugees. Education of Palestinian refugees is supported by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (hereinafter referred to as UNRWA)(UNRWA 2014). At the UNRWA school, which follows international educational trends, they don’t use mass teaching methods, in which the initiative is in the hands of the teachers and the classes center around one- directional cramming, memorizing, and recitation. Instead, the school promotes understanding by allowing students to experience firsthand activities that suit their individual interests and having them link those experiences to their own experiences, thereby attempting to improve classes and to guide students to autonomous and cooperative problem-solving (UNRWA and UNESCO, 2006).

On August 20th, 7 teachers and teachers’ consultants (teaching history 30 to 34 years) were asked to view the video material in a group, after that interviews were conducted. On 23 August, elementary school 3rd graders and middle school 2nd graders at the UNRWA school were asked to view the same video material, after that interviews were conducted.

Uzbekistan

In the education system of Uzbekistan, the 9 years of compulsory schooling is divided into grades 1 through 4 in elementary school and grades 5 through 9 in middle school. Classes in elementary school are directed by homeroom supervisors, whereas middle school classes are directed by subject supervisors.

Classes consist of about 40 to 50 students each. Since some schools lack classroom facilities, sometimes a single school building is shared by two schools; one uses the classrooms in the mornings, the other in the afternoons.

In this study, 12 teachers in the public elementary school and public middle school of Tashkent, as well as 9 students (in Grades 3, 6, 7, and 9), were asked to view video programs on August 29th, after that interviews were conducted.

The Philippines

In the Philippines, secondary education consists of 4 years, and this has been raising the following 3 issues in recent years. First of all, students’ basic academic skills are low, resulting in low ratings in international achievement tests. Secondly, students are mentally immature when they graduate high school at the age of 16, it makes difficult for them to find employment. Thirdly, because of the lack of basic academic skills, the graduates cannot find work in responsible managerial positions when they are employed overseas (JETRO, 2014).

The Philippine government is now working to resolve such issues on a nationwide level, not only by extending the period of compulsory education but also by improving educational content and methods. Traditional methods of schooling in elementary schools involved one-directional explanations by the teachers and indiscriminate memorizing of text-books. However, the significance of proactive speaking by students during class and lessons that promote independent thinking by students are starting to gain recognition.

Though the numbers are still insufficient, many schools in the country are now equipped with computers and projectors, and the environment for utilizing ICT is on its way to becoming fully established. However, the teachers using such facilities do not receive sufficient training, leading to abandoning of the newly provided computers in some cases.

On August 30, 2 teachers from local public elementary schools who are pursuing master’s degrees at the graduate school of Bulacan State University were asked to view the video material, then interviewed. On September 2nd, 6 teachers from a private elementary school on Leyte Island were asked to view the video material in the same way, then interviewed.

4. Results and Discussion

- 4.1. Results in Jordan (UNRWA School in Amman)

Of the educational video programs developed in Japan, science educational material has been found effective in school education supported by UNRWA. The following are the 2 reasons for this.

The first is that the topics covered in the programs are familiar to the students attending the UNRWA school. For example, “Marvelous Seeds” (target: grade 3) describes how seeds of plants growing in fields are transported by insects and wind. Since Jordan has a desert climate, it has no fields like those in Japan; however, in areas close to the Mediterranean Sea, there are some fertile green regions where similar insects abound, and the students are able to gain a good understand by forming a link between the program and their own experiences. Similarly, most of the equipment used in a variety of experiments conducted in the video program “Air that Surrounds the Earth” (target: grade 6) are available at the school, enabling students to view the program with a good understanding of the purpose of the experiments and the reasons why particular equipment is used. When this video program was shown to the students, they reported, just as the teachers did, that they found it easy to understand because they were familiar with the contents and methods used.

The second reason is that by enlarging images that cannot be easily seen in ordinary classroom learning, or by zooming out to present the total image of a target item, students are given a chance to come up with questions that they would not have come up with the traditional media (i.e. photographs and drawings in textbooks). This was also true for the teachers who took part in the study; they came up with many questions and findings when they saw the video material, such as “What’s this?”, “What is it doing?”and “It looks like the pollen on insect feet doesn’t come off so easily”. After viewing the video programs, the teachers pointed out the possibility of the students’ coming up with such questions on their own by experiencing what the teachers did. UNRWA’s aim is learner-oriented education, and since it promotes the students’ coming up with questions on their own, these educational video programs are expected to become a medium that triggers such reactions. Some practical comments are as follows: “The daily classes are conducted only through textbooks, chalk and talk, but video material enables deeper understanding and arouses the intellectual curiosity of the students” (Jordanian teacher C, teaching experience: 30 years). “Science is a subject that is readily understandable with the help of video material, and it is easy to come up with questions when they are linked to everyday situations. In regard to the language used, a deeper understanding of the contents can be promoted if the teachers can provide additional commentaries.” (Jordanian teacher D, teaching experience: 32 years).

On the other hand, further study on educational material is necessary to enable teachers to provide answers to the various questions that students come up with, and to use such questions to lead to the next steps in classwork. Though the science video programs show that the two countries have much in common, the fact remains that the targets of these programs are Japanese students; therefore, it is only expected that teachers would not be able to answer some of those questions. For example, ladybugs are common in Japan, whereas many teachers and students in Jordan have never seen one. Although there are similar insects in Jordan, considerations need to be made in order to determine what teachers should do when students take an interest in ladybugs, or how the teachers should use their questions to lead into lessons for classwork. Specifically, it was proposed that comments on significant words that appear in the video programs should be provided to the school. It was also pointed out that the target grades should be considered before the programs are viewed. For example, “Life on Earth” and “Air that Surrounds the Earth” are geared to the 6th grade curriculum in Japan, but the contents of this program are studied in the 2nd grade of middle school in Jordan.

It was also pointed out that if a cross-subject project-based learning situation was possible, instead of a subject-based class, such educational video programs could also be used to enhance English listening skills. However, the current curriculum in Jordan allows for only subject-based classes.

Studies on students showed that they made many positive comments on these educational programs, both in terms of understanding and interest levels. However, it was found that viewers of video programs targeting the upper grades had difficulty following the English commentaries, because there were so many commentaries. When used in schools, supplementary commentaries are available from the teachers, but when these educational programs are used for independent study, they will need to be translated into Arabic, their mother tongue. - 4.2. Results in Uzbekistan (Public elementary school in

Tashkent)

In a study conducted in an elementary school in Uzbekistan, 12 teachers teaching grades 1 through 6 took part in the research. All of them answered that they would like to use the video programs in their classes. The 3 reasons are stated below.

First of all, the video programs promote understanding among students. Education in public elementary schools in Uzbekistan is completely teacher-oriented, which may be a relic from the former Soviet Union days. However, teachers encourage students to be motivated, and interaction between teachers and students during class is frequent. During our visit, we saw students frequently raising their hands to answer questions from teachers. Though the education is teacher-oriented, the teachers make a point of interacting with the students, confirming their level of understanding as the lessons proceed. The classes are therefore not a one-directional transmission of knowledge. These teachers, who place emphasis on students’ understanding, expected the educational video programs to supplement areas that cannot be fully explained in class. The program contents were well suited to the curriculum used in Uzbekistan, and the leading opinion was that they could be used as they are in class. For example, the program “Creature at Our Feet” is suitable for the chapter on plant life, pollen and nectar. The teacher commented as follows: “In the regular classes, no matter how thoroughly we explain using the text-book, the students still find things a little difficult to understand. But when we use a video as we explain, it is more effective.” (Uzbek teacher G, teaching experience: 31 years). Regarding the program “Life on Earth” in which the cycle of carbon dioxide and oxygen in plants is explained in an easy-to-understand way, it was pointed out that the program content, which dealt with global warming, was suitable for both botany and chemistry classes. There was also the following comment: “If experiments can be conducted” after showing this program to the students, “it would be possible to arouse their interest even further” (Uzbek teacher H, teaching experience: 12 years). As such, there are high expectations for the program material as media suited for promoting understanding of the existing curriculum.

Secondly, the programs can be used as media that nurture students’ “listening”, “speaking” and “expressive” skills. The video programs become an indirect experience for the students, and draw out their comments and emotions. During this study, we witnessed scenes in which students who viewed the video programs asked questions, made remarks, and explained the program content. Upon observing such scenes, it seems that the teachers came to see media such as the educational video programs used here to be productive in drawing out questions and interest in the students and increasing communication among them. Since “listening”, “speaking”, and “expressive” skills can be nurtured in classes where spontaneous communication is generated, expectations for educational programs are believed to be high.

Thirdly, there is the expectation toward a new educational method. As described earlier, education in public elementary schools in Uzbekistan is teacher-oriented. In other words, classes are centered on teachers’ explaining the contents of text-books. In traditional educational methods, both the resources used by the teacher and the students are limited to text- books, so the classes are geared to whatever is in the text-books. However, by using our educational video programs, it is expected that classes will take on a new development that extends outside the borders of the text-books. (Uzbekistan has 5 state-run broadcasting stations, but very few educational programs are aired.) In an interview conducted after viewing of the video program, the teachers earnestly discussed questions such as, “What would happen if we started using educational video programs in class?” and “How should the coursework be designed if we were to do so?”

On the other hand, to enable elementary schools in Uzbekistan to make use of these educational programs, issues such as lack of facilities, language barriers, and understanding and designing of coursework to accommodate the use of educational video programs must be addressed.

In terms of facilities, most teachers commented on the lack of adequate facilities for viewing the video material, and pointed out the practical difficulties they face in the classrooms despite the high needs. Even though the school we targeted in our study is a standard public elementary school in Uzbekistan, there were almost no facilities in the classrooms. Some issues may be resolved by using portable terminals, such as iPads that do not rely on an external power supply, but since the viewing methods of educational programs provided by JAMCO are bound by copyright policies, reproduction methods (such as development and/or selection of portable terminals and data format) will need to be considered.

In terms of language, Uzbekistan is in a fairly complex situation. There are two types of public schools in Uzbekistan: one is taught in Russian and the other in Uzbek, and the students (and parents) select schools depending on the language used. Although only one of the two languages is selected at this point, it is critical that both languages be acquired for application to secondary and advanced education. Therefore, there is a higher demand for Russian than English, and texts translated into English are less convenient. The same can be said for use in school and independent learning, where texts have to be translated into either Russian or Uzbek.

Finally, we are faced with the issue of understanding and designing coursework to accommodate the use of educational video programs. Though the teachers show interest in using such material in class, the methods used in traditional textbook-oriented classes are not sufficiently effective in handling issues that may arise from using these video programs. There are many points that should be considered when designing the coursework, such as how to answer questions from the students that extend outside the borders of text-books, how to select video programs for viewing as supplementary material, and the timing for showing the programs. To become a teacher in Uzbekistan, one must graduate from the department that focuses on the subject of one’s specialization, then undergo a month of training provided by the government. These sessions offer training on teaching methods, but opportunities for designing coursework using video material are not available. We will need to provide seminars for studying class methods, similar to those held in Japan, while enabling teachers to build foundations on which they can develop their own classroom methods. - 4.3. Results in the Philippines (Bulacan & Leyte Island)

While viewing the video material, the teachers discussed the points being emphasized in the program, and the best ways to communicate with the students during class. In the end, all teachers answered that the video material would be beneficial to the students, and that they would like to use it if the contents suit their curriculums, as they expected the video programs to encourage learning. In addition, we received the following comments: “The programs make good use of their video features.” (Filipino teacher A, teaching experience: 5 years) and “You would not be able to see such images if you were observing the actual phenomena.” (Filipino teacher B, teaching experience: 13 years).

Motivated teachers have been known to download science materials from the Internet for use in class. These teachers have stated that science video programs are especially helpful in motivating students, since they enable students to see phenomena in fast forward or slow motion. We found that the teachers would be strongly interested in using the video programs because if liberal use of the internet were available to conduct online searches in line with the curriculum, such programs can be effective in improving the level of education.

Even though the environment for video-viewing is not yet satisfactory in elementary schools in the Philippines, it is improving, with ICT equipment being installed in some places in recent years. However, in order to use such equipment, teachers are often required to take preparatory procedures, such as carrying the equipment to the designated classrooms.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to investigate how educational video programs owned by JAMCO are understood and interpreted in developing countries, in order to clarify the possibilities and issues regarding the secondary use of Japanese educational video programs in these countries. Studies were conducted in August 2014 in Jordan, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines.

Research results showed that, despite requests to have the programs translated into local languages, they can be used satisfactorily in English as classroom material. Several issues in the designing of coursework were clarified through the research, such as how teachers with no experience in using educational video programs should incorporate them into class, what kind of questions the teachers should ask as the students watch the programs, and when to make time for students to think things over.

Although Kodaira (1994) proposed preparing textbooks for teachers, incorporating educational video programs into classroom education means that the entire coursework structure is bound to change. Simply handing over such video programs as classroom material may prevent teachers from fully appreciating the significance of such material and making use of it. Therefore, training in designing coursework should be provided when the programs are provided. In other words, when we provide the programs, we will need a system that also provides opportunities for workshop training in using educational video programs in class, as well as seminars where teachers can sit in classes using educational video programs and discuss the contents of the coursework among themselves.

Reference

- Cole, Charlotte Frances (2009) “What Difference Does it Make? : Insights from Research on the Impact of International Co-Productions of Sesame Street” , NHK Broadcasting Studies No.7, pp.157-177

- Ichikawa Akira (1990) “Kaihatsu tojokoku ni okeru kyoiku bangumi kaizen no joken to seisaku gijutu kyoryoku no kadai [The Study of the Requirements for a Training System for Educational Television supported by International Cooperation]” , Hoso kyoiku kaihatsu center kenkyu kiyo (Bulletin of the National Institute of Multimedia Education) 4, pp.41- 68

- Kodaira Sachiko (1994) “Taikoku ni okeru NHK terebi kyouiku bangumi no kouka – shougakusei wo taisho to shita chousa kara [The effects of NHK television educational program in Thailand – findings from a study on elementary school pupils -]” Hoso kyoiku kenkyu 19 , pp.19-44

- Kodaira Sachiko (2009) “Kodomo muke kyoiku media no kenkyu igi [The significance of research in educational media for children]” , Hoso kyoiku to chosa May issue, pp.82 -101

- Konno T., Kishi M., Kubota K. (2012) “The Conflict and Intervention in an Educational Development Project: Lesson Study Analysis Using Activity System in Palestinian Refugee Schools” Educational Technology Research Vol.35 (1,2), pp. 43-52

- Konno T., Miyake K., Kishi M. (2014) “How to Improve the Effective Uses of the Blackboard Through Lesson Study in India?” 10th Annual International Conference of the World Association of Lesson Studies, Bandung Indonesia.

- Nu Nu Wai, Kubota K., and Kishi M. (2010) “Strengthening Learner-Centered Approach (LCA) in Myanmar Primary School Teacher Training: Can Initial Practices of LCA BE Seen?” International Journal for Educational Media and Technology., 4(1), pp.46-56

- MEXT (2013). “Kokusai kyoiku kyoryoku [International cooperation in education]” , http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/kokusai/kyouiku/main5_a9.htm (retrieved on Nov. 30, 2014)

- Sato, Manabu. (1997) “Kyoushi to iu aporia – hanseiteki jissenka [The Aporia of being a teacher – a reflective practician]” , Seori Shobo

- Yamada, Shoko (2009) “Kokusai kyouryoku to gakko [International cooperation and schools]” , Soseisha

- UNRWA (2014) http://www.unrwa.org (retrieved on Nov.30, 2014)

- UNRWA and UNESCO (2006) Quality Assurance Framework for UNRWA Schools 2006. UNRWA/UNESCO Department of Education, UNRWA

- JETRO (2011) “Kiso kyoiku wo 6-4 sei kara K-6-4-2 sei e [Reforming fundamental education from the 6-4 system to the K-6-4-2 system]” (Report from Overseas Research Associate), http://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/Publish/Download/Overseas_report/1106_suzuki.html (retrieved on Nov. 30, 2014)

*Links are for posted items. It is possible that some items are not currently available or are being edited.

Takayuki Konno (Meisei University)

Makiko Kishi (Meiji University)

Kenichi Kubota (Kansai University)

Takayuki Konno

| 2014.4- | Assistant Professor, Department of Education, Meisei University |

| 2012.4-2014.3 | Instructor, Faculty of Studies on Contemporary Society, Department of Media Presentation, Mejiro University |

Makiko Kishi

| 2013.4- | Assistant Professor, School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University |

| 2010.4-2013.3 | Researcher,international research institute for studies in language and peace , Kyoto University of Foreign Studies |

Kenichi Kubota

B.A. (Physics) 1973, Chuo University, Tokyo, Japan

M.A. (Instructional Systems Technology) 1986, Indiana University

Ph.D. (Instructional Systems Technology) 1991, Indiana University

Return to 23rd JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 23rd JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page