25th JAMCO Online International Symposium

December 2016 - June 2017

The Current State and Challenges of International Broadcasting in Key Countries

Global film and TV distribution policy disputes and overseas development of Japanese TV programs

- Overseas development of Japanese TV programs in the 20th century was largely an aspect of the country’s “international exchange” program. Little thought was given to commercialization. Time data exists thanks to ICFP surveys, but there is only a scattering of data on a value basis.1

- There have been long-running, fierce discussions between the US and Europe about international distribution of movies and television programs. Japan, however, has not been part of these debates.

- In terms of policies for developing Japan’s film and television industry, there was a turning point in attitude in the 2000s and in government budgets in the 2010s. It became possible to gather statistics about overseas sales of TV programs on a value basis.

- Policy investment has had an impact. Spending on international development in Japan’s film and television industry has increased to the point where they will soon reach Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s targets. Companies’ business models have also evolved.

0. Outline

Japan’s video (TV programs, movies) exports increased in the 20th century in terms of hours.2 However, much of this was based on non-commercial activity, including free-of-charge government cultural cooperation and provision of programs by the Japan Foundation and the Japan Media Communication Center (JAMCO). As regards prices of anime, which was Japan’s mainstay film and TV export, most anime producers recall that when large amounts were exported-for example in the 1980s, when broadcasting was privatized in European countries and when the broadcasting market, including cable and satellite broadcasting, expanded worldwide-almost all were priced at levels that did not generate profits. In exports of drama as well, as Oba (2016)3 notes, in the 1970s, “Japanese companies had hardly anything to do with it. Most of the drama exported to countries in Asia consisted of ‘TV movies’ shot on film by film companies.” At the very least it is questionable whether broadcasters were aware of the commercial value of overseas sales of TV programs. Public broadcaster NHK’s “Oshin,” the most famous example, was also rolled out in most countries within the framework of the international cooperation/support programs mentioned above. Policy involvement in overseas sales of film and television was within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ framework of international cooperation and friendship programs and there was little public involvement or private awareness of the business potential or commercial possibilities.

In the 21st century, the establishment under the Koizumi administration in March 2003 of an Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters within the Cabinet Office was a turning point in terms of attitude toward content policy and expansion of overseas sales. Alongside patents, content also became a target of measures due to, “the need to strive to make Japanese industry more internationally competitive.” A short time before, in January 2001, a Media and Content Industry Division had been established within METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). Subsequently, the Agency for Cultural Affairs submitted the largest budget (around ¥2.5bn, FY2004) based on its Japanese film promotion plan. Later, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) upgraded its promotion of content distribution office to the Promotion for Content Distribution Division. It became possible for MIC’s Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP) to gather data on overseas program sales such as the data presented later (until then there had only been sporadic surveys and estimates). The 2000s thus saw a turning point in terms of attitude.

The 2010s have seen a turning point in terms of the size of policy budgets, as we shall see. Targets, which are having an economic ripple effect under Abenomics, policy investment exceeding several billion yen annually, sales, and other items are nearing those in major European countries. These turning points in awareness and budgets this century call to mind various policy disputes, cooperation, and competition within the structure of the US versus France, Canada, continental Europe, South America, and others that has continued for close to 100 years since the interwar years in international markets and international development of film and television (and thus in package products and producer genres). Japan for better or worse has been distant from all this. However, if we seek greater expansion, we shall have to act with awareness of these global trends.

1. Brief history of content policy disputes

Despite its peaceful image, film and television has long been a bone of contention between Europe and the US in terms of government policy.4 This first emerged when Europe had been devastated by the First World War and the film trade between the US (Hollywood) and Europe was quite unbalanced. The film industry in America had promoted the so-called flexible manufacturing system, based on a model of “Specialization and Division of labor” in film industry (actors, production teams, camera, lighting and sound recording, art department, etc.) and had moved from small-scale production to a mass-production system, which was highly efficient and yielded cost benefits. Film and television trade issues and disparities in competitiveness have remained political problems to this day. Europe introduced import restrictions, high import tariffs, screen quota systems5 and the like, aiming to curb imports from the US and protect European countries’ own film industries, while the US, under the slogan “Trade Follows the Film” strove to expand trade for US products as a whole via the awareness boost that film provides. This US concept is essentially the same as the current Cool Japan concept.6

This remained the case after WWII. The political confrontation between east and west during the Cold War boosted shipments of movies from the US to devastated postwar Western Europe for ideological reasons. It goes without saying that along with the global spread of television, gradually there was political debate not only about movies but also about TV programs. During the 1980s, when European broadcasters were privatized, the flood of exports of Hollywood dramas and Japanese anime also became an issue. At the end of the 20th century, Hollywood movies were one of the few trade categories in which the US, facing twin deficits, had a trade surplus. Movies were an item in which the US had to protect its competitive advantage. The countries that suffered from unequal trade with the US were not just in Europe, but also included Canada and countries in South America and Oceania. The situation was especially serious in Canada, which adjoins the US and shares its language and culture. Canada, which also has a French speaking region, tends to be in sympathy with France on this issue. This is where the structure I mentioned at the outset-of the US versus France, Canada, the European continent, South America and other countries-arises.7

The dispute between the two sides has been conducted via negotiations between countries, but in the main it has now moved to international negotiations. The location may change-The Uruguay Round of the GATT in 1986-94, WTO trade in services negotiations in the 90s, the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in the 2000s, FTA negotiations between the US and EU in the 2010s-but the discussion continues. However, the dispute, having begun in the interwar years, is now nearly a hundred years old. Its roots run deep and if it is treated simply as a trade issue or a cultural or ideological problem, or one to do with expression, it will probably remain difficult to solve.

2. Measures

In countries such as France, various measures, ways of dealing with competition, and cooperation have been adopted, as follows.

[Government regulation frameworks]

Regulation of (volume) of imports from overseas,

screen and broadcasting quotas (for example, the EU’s Television Without Frontiers Directive is well known among broadcasters),

obligation to invest in and broadcast locally produced movies and programs in certain genres.

[Government promotion framework]

Systems of incentives, such as subsidies systems, tax benefit systems.

Continental Europe is home to numerous international co-productions. Incentives to promote this have been adopted in individual European EU states and at the EU level, the aim being to boost competitiveness vis-a-vis the US via cooperation.

There is also cooperation with the US. Attracting US film and television crews, whose production costs are a digit higher than in other countries, at least provides employment and earnings opportunities for local film and television production companies. However, it also creates opportunities for exchanges on a personal level in terms of technology and production. There are many film commission services around the world that have set up incentive schemes with the condition that they support this. In many cases governments and the like have provided financial support for such schemes. Moreover, if the demand is for a ripple effect that promotes film (content) tourism8, co-productions with US companies, which have global distribution and transmission networks, is more likely to be effective.

3. Discussion points

It is possible to highlight various points in the history of competition, cooperation, and government disputes in the structure of the US versus France, Canada, South America, and other countries and regions mentioned above. In the following I summarize these points and their background. I expect the discussion of these issues to become even more complicated, especially from 2017 in the “post-truth” era.

3-1 Trade issues

Film and television exports generate a substantial surplus9 for the US. Almost all countries other than the US and the UK run film and television trade deficits. Japan is believed to have built up a major import surplus10. The subject of free trade versus protectionism in international trade has been discussed with respect to all items and areas. However, one could say that film and television has been a central area of discussion within the field of cultural exceptions.11 Whether it should be on the agenda was questioned in the US-EU trade talks in 2013. At UNESCO in the 2000s, in discussion of the Cultural Diversity Convention, France strongly approved of countries’ measures to protect their cultures. In other words, it is actively developing measures that could become non-tariff barriers.

3-2 Economic and political structures

Film and television are clearly goods/services that strongly communicate views, ideas, and cultures that have a major impact on political and social structures. This makes me want to treat them quite differently than simple commercial goods and commodities. I think the relative position of economic and political structures (e.g., democracy that cannot be separated from freedom of speech) was to some extent questioned in the inter-governmental negotiations mentioned above. In other words, I think that in the US, extreme individualism is demanded in both economic and political structures as the structures are based on individualism, while among the countries opposing the US, especially France, the democratic political structure model is independent of, or superior to economic structures. The key word in France’s assertions is diversity. From a freedom of speech perspective, ideally people should be provided with diverse ideological choices (and pluralism). However, market mechanisms do not always guarantee diversity. They can even bring about oligopolization. Europe suffered from Hollywood’s domination of the global market, which can be seen everywhere now, and from the resulting disadvantages.

Factors that make this discussion even harder to understand are the practical aspects of film and television (e.g., reporting disasters, election reporting) and their aspect in entertainment, as well as their dual aspects of high and popular art. There is no clear dividing line between these two aspects, and what was once popular art can later be regarded as high art (cf., opera,Japanese kabuki). Most content has these two aspects to a greater or lesser degree. The problem is that the strength of the necessity of the demands that come from the freedom of speech model differ between the former and the latter, and that differences also arise in terms of approval of government involvement.

3-3 Government policy with regard to industrial organizations, structures

The global spread of television in the postwar era was a major impact for the film industry. The new visual medium was a threat to film’s monopoly of visual media. I think it is important to closely monitor the history as it is easy to imagine the same thing happening with broadcasting and the internet now.

Japan, the US, and Europe responded in very different ways to the advent of TV. In Japan, in 1953, five major Japanese film companies concluded an agreement, pushing film and television into a confrontational relationship.12 In the US (excluding news), Hollywood strove to win television production business. This can be said to have culminated in 1970 with the drawing up of the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules13, which caused TV networks to lose the incentive to produce and own packaged programs. European governments also intervened in this area. They established public systems to support film within the broadcasting industry. If you look in the cash flow of France’s CNC subsidy scheme at the balance of subsidies and tax benefits received and special taxes paid by film companies and broadcasters each, it becomes clear that broadcasting supports film making.14 Broadcasters are also obliged to invest in film in proportion to the size of their annual revenues. Another example is the establishment on 2 November 1982 in the UK under Margaret Thatcher’s government of Channel 4, which invests in independent film production and was charged with the provision of high-quality innovative, distinctive, diverse, and educational programming15. The UK had also had film subsidy schemes involving relatively substantial amounts such as the Eady Levy16 . However, due to a shortage of funds and the Thatcher government’s overall policy there were calls to scrap them (started in 1957, scrapped in 1985). There was a shift from direct subsidies to broadcasters supporting film making.17

Various interpretations are possible after the fact. Such structures can be interpreted as arrangements that force the “lucrative popular media” of the day to support “high-art movies.” In fact, the quality of broadcast programs at the dawn of the new TV era was a long way from that of film, and even today, movies take more time to make and have higher budgets than television programs. Broadcasters sought to obtain broadcasting rights for movies, viewing them as killer content for their program schedules. To put it more abstractly, when a zero sum game-like situation arises between traditional and emerging industries as a result of changes in the business climate such as new technology, governments often accelerate such changes and facilitate them by designing systems and institutions. In Japan, nothing was done. However, in the US and Europe there was a strong move toward rent seeking18 by defensive industries.

Efforts to change business organizations’ business models and promotion policies seeking to benefit from the ripple effects of relationships between industries have taken the following forms since the 1990s:

- – sequential diversification of package deals (both movies and TV) into other media (the so-called windowing strategy),

- – development of copyright business leveraging copyright elements of items such as books, goods, and soundtracks, and

- – development of film tourism, content tourism, and seichi junrei (film pilgrimages in Japanese).

As film and television outlets and media become diversified (because audiences become dispersed) management needs to become diversified. There is no established business model anywhere in the world. I think this is fair as a way of seeking a solution.

4. Japan has been an outsider (in a good sense)

It would not be going too far to say that Japan has stayed out of the abovementioned international disputes and that the Japanese government and Japanese industry are uninvolved (rather, in Japan, problems of disparities in terms of competitiveness and ability to transmit information take the form of “Tokyo versus local areas/regions.” This resembles the situation in which the US is in dispute with France and other countries).

As an outsider, until at least the end of the DPJ era (till 2012),

- – there were no restrictions or special taxes relating to film and television imports and exports.

- – there were no domestic systems favoring domestically produced content such as screening and broadcasting quotas.

- – The budget for promotion of domestically produced content was around ¥4.0bn, on par with midsize countries in Europe (see below).

- – Via the Structural Impediments Initiative (SII) talks, the US-Japan Framework Talks, the US-Japan Regulatory Reform and Competition Policy Initiative, and the US-Japan Economic Harmonization Initiative, domestic laws, such as copyright law, had come relatively close to US systems, and

- – the policy focus with regard to media tended strongly to be on distribution channels rather than content production.

Because of this, Japan did not become embroiled in the dispute between the US and Europe. In other words, just as there were no WTO/FTA-type tariff or non-tariff barriers in film and television that were obstacles to free trade19 , Japan’s domestic film and television market was based strongly on free competition, including domestic productions and imports. However, as aggressive protection and support policies of the type discussed in the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity have been modest in relation to the size of the country, in Japan, this issue did not become an international problem. International co-production agreements between countries20 were also rare, and a sense of exclusivity in relation to other countries was not created.

However, to avoid any misunderstanding (rather than my unclear view outlined above), Japan’s legal stance in relation to WTO/GATS is that it is, “opposed to the argument that measures for protecting the “cultural value” of audio-visual services should be allowed as GATS exceptions, because audio-visual services represent a major area of trade in services and excluding them from the scope of GATS based on the ambiguous concept of “cultural value” would be inappropriate.”21 On the other hand, it has failed to ratify the UNESCO declaration. In other words, superficially Japan has adopted a stance similar to that of the US, its measures vis-a-vis content being more industrial than cultural. This has continued under the Abe administration.

In all this I think I should note that Japan’s domestic market is quite a free one in institutional terms, both for domestic productions and imports (of course the natural barrier of the Japanese language cannot be ignored). The eyes of this trained audience can appeal internationally, I think.

5. Before and after December 2012

I think the start of the Abe administration (in December 2012) was a major turning point for the Japanese government’s content policy. A special feature of the policy was that it stressed “broadcasting content” and “local content” among various (media) content.

5-1 Budgets

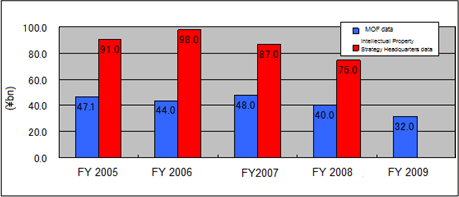

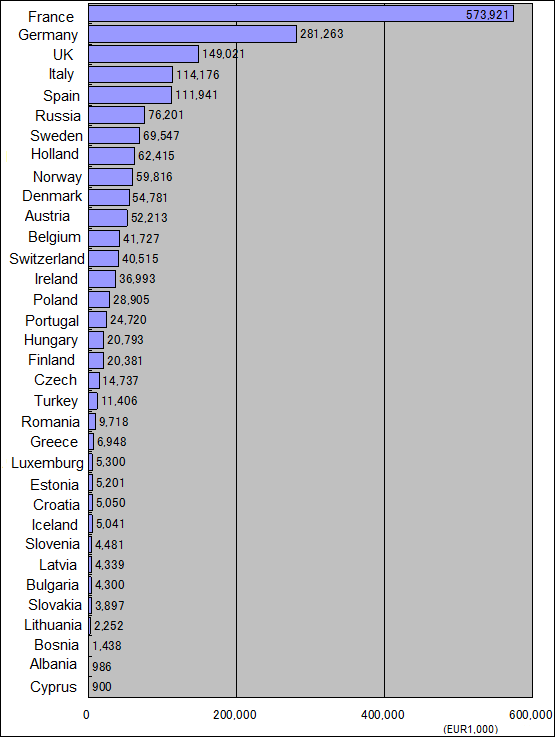

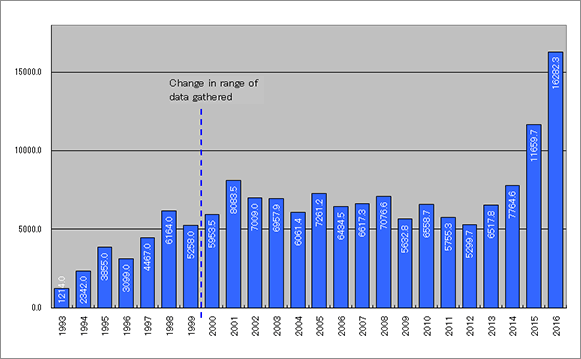

In the mid-2000s, Japan’s central government’s budget for promotion of content, taken from general revenue, was around ¥4.0bn or ¥9.0bn, depending on how the data is totaled up (Figure 1). This was less than in major European countries but on par with midsize ones (ranging in size from Poland to Holland) (Figure 2).

Figure1: Spending to promote content in Japan

(Sources: Secretariat of Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters, outlines of draft intellectual property related budgets (various years); METI, Statistics Bureau, draft government proposals, reference material (government), various years. With regard to data from the Secretariat of Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters, figures taken from the Japan Brand section of the overall Content business framework.)

Figure2: Total fund income by country

(public funding,2005-09 average; unit: EUR1,000)

(Data: Sunsan Newman-Baudais,(2011) Public Funding for Film and Audiovisual Works in Europe 2011 Edition. A Report by the European Audiovisual Observatory. p23)

Part of the content budget was also a target in the “work classification” conducted in the Government Revitalization Unit of the Cabinet Office under the DPJ administration in 2009 and 2010.22 There was no expansion as government policy, including subsequent responses to major earthquakes.

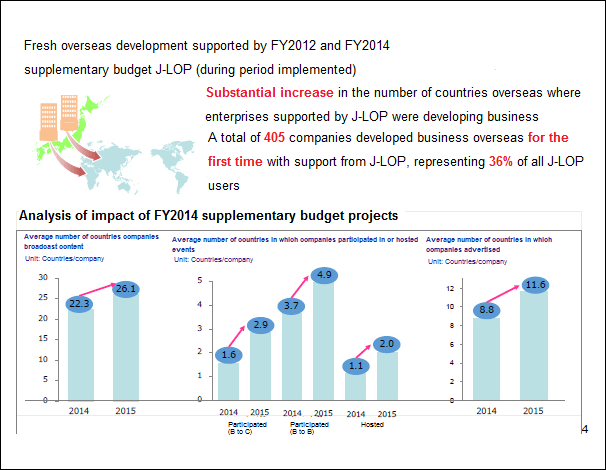

After the Abe administration took office in December 2012, a major subsidy scheme called J-LOP, which was based on the FY2012 supplementary budget, was announced. (Figure 3). The budget was of the order of several billion yen per year. This was of course far larger than any previous budget in the history of Japan’s measures relating to film and television content. Initially, METI and MIC jointly managed the scheme. Today, however, it is a fund or subsidy scheme run by METI’s Media and Content Industry Division (subcontracted out to the Visual Industry Promotion Organization (VIPO)). The budget is not limited to film and broadcasting but is also used to subsidize localization (subtitling, dubbing, including music and games) and promotion (exhibition in international trade fairs) (subsidy ratio: 1/2, later 2/3 in some cases).

Figure 3 J-LOP fund, subsidies by METI

| Abbreviation | Period in effect | Official name | Budget |

|---|---|---|---|

| J-LOP | 2013.3-15.3 | FY2012 supplementary budget, METI, MIC fund for “Promoting Content Worldwide” | ¥12.33bn (METI), ¥3.20bn (MIC) |

| J-LOP+ | 2015.3-16.3 | FY2014 supplementary budget METI “Fund for promoting content produced by Japanese broadcasters worldwide that contributes to regional revitalization” | ¥5.9bn ¥97.44mn |

| J-LOP | 2016.2-17 years | FY2015 supplementary budget, METI “Subsidy for expenses arising from establishment of foundation for distribution of locally produced content overseas” | ¥6.6bn ¥94.00mn |

| J-LOP4 | 2016.12- | FY2016 supplementary budget, METI “Subsidy for expenses arising from establishment of foundation for creating global demand for content” | ¥5.9bn ¥99.00mn |

Of course J-LOP was not the only major budget. MIC’s content promotion division runs programs focused on developing overseas sales of broadcast programs in the formats shown in Figure 4 below. The targets of the subsidies are businesses whose central focus is developing overseas sales of broadcast programs.

Figure 4: The policy budget of Promotion for Content Distribution division of MIC

| FY implemented | Budget (¥bn) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | International coproduction to promote the content business in overseas markets | 15.04 |

| 2014 | Model project to strengthen and promote the broadcasting content business in overseas markets | 21.00 |

| 2015 | Project to support the expansion of the broadcasting content business which contributes to regional economic revitalization into overseas markets | 16.50 |

| 2016 | General support project for the expansion of broadcasting content business in overseas markets | 12.00 |

| 2017 | Establishment of foundation for broadcasting content business in overseas markets | 13.40 |

6. Recent results

6-1 Overview

We introduce quantitative results of these policies in the next section. However, two highly significant results are (1) companies that were unaware of overseas business have been given opportunities to experience it (Figure 5) and some are trying aggressively to commercialize it, and (2) NHK (NHK Enterprises), major private broadcasters, and other bodies that have long been involved in marketing programs abroad have been given the opportunity to pursue business models on a new level (see next section).

When a new form of media is born, film and broadcasting experience audience and revenue breakup. As a result, they have to diversify their products, as typified by the windowing strategy, and secure diverse revenue sources. The advent of TV in relation to film was the first example of this. Subsequently, the film and television industries experienced this with the advent of home video, cable, and satellite broadcasting, and they are now about to embark on full-fledged competition with the internet. Many private-sector broadcasters depend on broadcasting business for at least 90% of their revenue. To some extent they have to consider expanding non-broadcasting revenue and management diversification. Marketing programs overseas is one aspect of their efforts to diversify.

Figure5: Reference: Impact of historical J-LOP projects

Source: METI materials p4, Cabinet Office intellectual property strategy headquarters assessment, evaluation, and planning committee, content area meeting (second) 22 November 2016.

6-2 Quantitative results

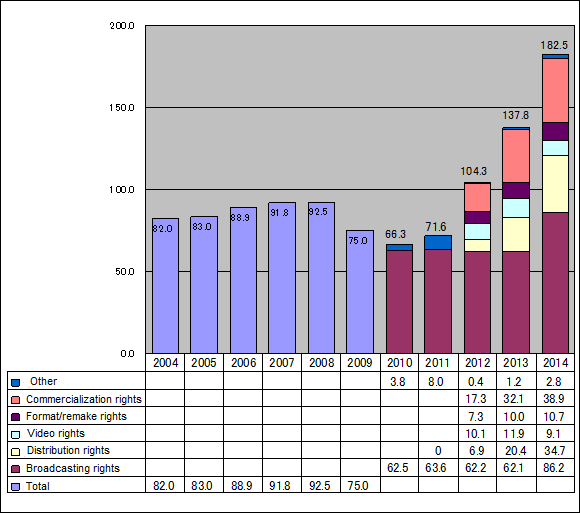

Overseas sales (by value) of Japanese TV programs have been firm, recently reaching new record highs. This is due to:

- – the industry as a whole, including not just key broadcasters but also regional broadcasters and production companies, being more aware of the overseas market due to substantial increases in subsidies,

- – yen weakening from 2012 through early 2016 (the period of the data below),

- – the emergence of an internet distribution bubble in the global market, with a knock-on effect in Japan, especially on anime.

Figure6: Terrestrial TV program exports (¥bn)

Source: MIC, Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP) Media sofuto kenkyuujo [Media software research institute], each year

In terms of policy, Prime Minister Abe, in speech given on 17 May 2013, talked about his growth strategy, which aims to triple TV program export value (to around ¥20bn) in five years. If current trends remain in place, this target looks achievable barring an “economic crisis on par with the Lehman Shock” or a “natural disaster like the March 2011 earthquake.”

There has long been demand for internet distribution in the sale of programs overseas, especially in emerging markets and the BRICS countries. However, transaction rates via internet distribution are low, and sellers handled it as accompanying broadcasters’ broadcasting rights option. However, due to the full-fledged entry and aggressive activity of global players such as Amazon Prime and Netflix, supply-demand in the global market is expected to change, as are transaction rates. Moreover, as shown in (Figure 6), over a short time frame, the value of internet distribution has exceeded that of video conversion rights. This trend has been seen in exports of both TV programs and Japanese movies. In 2015, the value of film exports rose sharply (Figure 7). Exports have expanded to all countries, including America and Europe, and especially China and countries in Southeast Asia. I estimate that distribution of anime in particular has increased.23

Figure 7: Exports of Japanese motion pictures (unit: $mn)

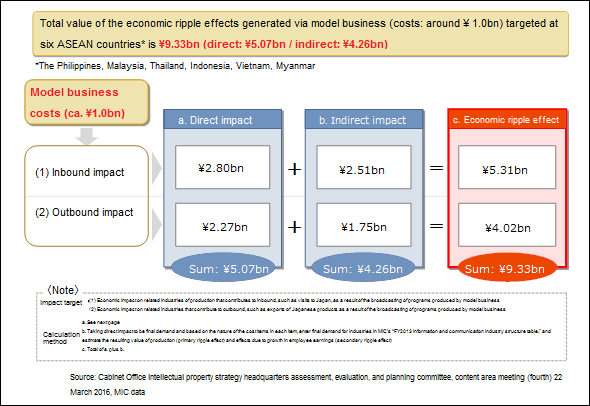

MIC releases data on the ripple effect based on a general industry-related analysis, and the figures are firm(Figure 8).

Figure 8: Economic ripple effects model business for developing sales of broadcast content overseas

Source: METI materials p4, Cabinet Office intellectual property strategy headquarters assessment, evaluation, and planning committee, content area meeting (fourth) 22 March 2016.

6-3 Assistance from environmental factors

Today, a worldwide (film and television) internet distribution bubble is said to have arisen. Such bubbles have arisen in the past. In the 1980s, when the European broadcasting market was privatized and the market opened up, and in the 1980-90s, when cable and satellite broadcasting expanded, due to major institutional (e.g., market privatization) and technological (new transmission channels, technology standards, etc.) changes, B2B demand for film and television content rose sharply. When the broadcasting market expands sharply, if due to cost and time considerations programs are not also sourced externally in addition to in-house production, then the number of programs is not sufficient for programming purposes. This is happening today in internet distribution in the form of lineup expansion.

Film and TV is also vulnerable to macroeconomic trends. From the perspective of buyers, the rationality of buying based on the major options of buying externally or making programs in house is important. Outstanding high quality and originality of content that is difficult to replace, cost-benefit, production/procurement time savings, and forex problems also cannot be ignored.

Compared with movies, TV programs focus more on regions and feature local content and it is hard for programs made overseas to enter the slots broadcasters focus on such as prime time and golden time. Broadcasting (rights) of Hollywood movies were an exception, but even they have lost a slot in the ultra-long term. In fact, foreign-made programs are mostly broadcast on multichannel networks, during weekdays and in the early hours of the morning. As a result, sellers who can supply “large volumes at low prices” have an advantage. This was one of the factors behind the strength of Hollywood dramas and Japanese anime.

6-4 Business model evolution

Typical internationalization of management is thought to evolve by stages, from product imports and exports to development of sales bases overseas, investment in production bases overseas, and trans-national management. In Japan, there are industries, such as the automobile and consumer electronics industries, that are already engaged as multinational corporations in activities that are not limited to Japan and that are practicing what in known in management studies as trans-national management. Similarly, in the world of content, Japan’s console game industry (Nintendo, Sony, etc.) has reached this trans-national management area, established bases in key regions around the world, and has built local companies and obtained local licenses to realize local production for local consumption.

Broadcasting is a business that requires approval or license from public sector in all countries, and even if content such as news genre needs to be exchanged, it was difficult to move business as a whole to other countries. However, the environment has been changing and it is no longer unusual for major companies or stations in one country to move to another country on a single-channel basis (e.g., cable and satellite channels). Package programs are to some extent international activity accompanied by commercial considerations (as in the case of Hollywood movies and TV dramas) and it is not unusual for companies to be aware of this.

Figure 9 the evolutional stages of program export in international management theory

| Typical internationalization of management | In the case of broadcast programs |

|---|---|

| (1) Demand from overseas and exports of finished products from the country | Complete package exports, footage sales |

| (2) Establishment of overseas branches, local distributors ((2)’ Partial transfer of expertise overseas) (3) Core expertise (manufacturing processes from manufacturing) transfer, major overseas investment |

Leverage capabilities of agents vis-a-vis other domestic companies, set up local sales bases (tie-ups with major local companies) local sales bases (tie-ups with major local companies) |

| Remake rights & format sales with no after-sales service Establishment of local sales bases (investment by company itself) International co-productions Remake rights & format sales with after-sales services Establishment of local production bases |

|

| (4) Local development structure (4)’ Establishment of local distribution organization |

News gathering and production for local consumption by local companies (owing channels and networks overseas, e.g., BBC-wstv) |

| (5) Trans-national operation |

(1) Sale of finished programs, footage

Even automobile and consumer electronics companies did not become trans-national businesses overnight. They also started with modest exports of products manufactured in Japan. Thinking about exports of goods and services not limited to the sale of programs, the first thing that comes to mind is exports of finished products. In the case of program sales as well, finished program packages are sold to overseas companies via some method or other and are broadcast locally after being localized.

There is also footage sales, The BBC Motion Gallery being a typical example. It is currently run by Getty Images24. Before Getty, it was run by T3MEDIA. Since then, Japan’s NHK, Fuji Television Network and other companies have participated and it is now a huge global node site for footage sales. The BBC, which represents the UK and has a global news gathering network, is also committed to securing and providing footage. Footage is secured via methods that include purchasing from communication companies, exchanges via broadcasting federations around the world, and exchanges with affiliated overseas broadcasters. BBC Motion Gallery is a trading site with direct participation by key broadcasters worldwide.25

(2) Development of reliable distribution channels, partial relocation of expertise overseas

When widespread expectations of sales growth arise, the problem of strengthening international distribution channels comes up. In the process, if commercial practices that view reliability as important are followed, as in Japan, business partners come to be selected. Similarly, in the world of overseas program sales, companies frequent major trade fairs such as MIPTV/MIPCOM as visitors and can pinpoint reliable agents and buyers after a number of test sales. While they may now be called key Tokyo-based broadcasters, it appears that Japan’s major broadcasters struggled for many years to build reliable distribution channels and today they appear to have selected partners.

(3) Relocation abroad of core competence, expertise, major overseas investment

In the next phase, risk arises, including overseas investment and relocating resources overseas (e.g., in manufacturing, moving some plants abroad). In film and TV program marketing, transferring formats and scripts and further expanding local distribution bases, including expanding branches and marketing companies are considered. Formats and scripts include transfer of drama scripts and sales of remake rights and the transfer of “bible” for variety / reality shows, in other words format sales. Tokyo and Osaka-based broadcasters are mainly focused on this stage.26 In the sale of remake rights and formats, sometimes post sales services are provided in which the original producer provides aftercare in the form of production advice. When this is realized, opportunities arise for exchanges between producers rather than between marketing staff. This sows the seeds for co-productions. International co-productions in Japan include:

- – format joint productions between major Japanese broadcasters and US and European production companies,27

- – remakes of Japanese dramas in Asia, elsewhere,

- – joint news gathering, production arising from provision of support for news gathering to foreign crews by regional broadcasters,

- – documentary genre pitching market, as seen in Tokyo Docs.28

In addition, there is also investment in local companies and direct investment in local production companies. Some Tokyo-based broadcasters have started to invest in Greater China and Southeast Asia.Tokyo Docs.29 Of course these were also measures to resolve problems peculiar to China, such as dealing with censorship imposed by radio and television authorities and problems of illegal distribution. However, expectations of the huge Chinese market are enormous. Southeast Asia is the de facto key region for the current Cool Japan campaign.

In addition, in terms of overseas investment, locally there are companies engaged in distribution company investment (channels and networks and/or broadcasters that have transmission lines). As regards broadcasting to local expat audiences by national/public broadcasters, there are examples of development of channels and services for cable, as well as satellite, local multi-channel, and international broadcasting. In Japan, it is possible to view Korean, Brazilian, and Hong Kong channels via cable and Sky PerfecTV! Companies broadcasting from Japan include JET-TV (Japan Entertainment Television Pte. Ltd. established in 1986 by Sumitomo Corp, TBS, MBS, HTB, and local Taiwanese investors, which focuses on Asia, but is currently developing from being a broadcaster of Japanese programs to being a general broadcaster), JIB (Japan International Broadcasting, Inc., in which NHK, TV Asahi Holdings, TBS, NTV, Fuji Television Network, and Microsoft have stakes), and WAKUWAKU JAPAN (in which Sky PerfecTV! JSAT, and Cool Japan Fund Inc. have stakes and which is based in Indonesia). Japanese language channels are also broadcast aimed at people with Japanese ancestry and expats in Hawaii and the mainland US (although the capital is American).

(4) Trans-national operations

The ultimate type of overseas development is the local production and consumption, trans-national business model, of which BBC Worldwide is a typical example. The initial concept of BBC Worldwide may have been to develop BBC programs overseas, and, as a cable and satellite network establish subsidiaries/local companies and provide a service for expat British citizens. However, notwithstanding that the US and Great Britain share a common language and culture, with BBC America gathering news and creating programs locally and boasting around 76.87mn subscribers (as

Figure 10: Evolutionary model of program sale overseas

| Image | To improve production (excluding productions targeted solely at domestic audience) | Prices | Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trade Fairs | Sales Channels | ||||

| ↓ | (Local broad-casters) | Production with quality control by overseas majors. Secure volume as goods for sale, mass-production structure. Training, for example at Tokyo Docs. |

Low profitability. Overseas activity having factored in aims other than profits, such as local motivation. |

Participation in regional trade fairs (ATF, TIFFCOM, etc.) Joint displays in the JAPAN booths at major trade fairs (MIP, etc.) |

Contract out reliable parties. Who? Key broadcasters? Trading companies? Agents? Other? |

| ↓ | Understand overseas tastes via international co-production (All-Japan brand support) |

Need for affordable pricing (in order to expand intellectual property) (e.g. Japanese anime in the 1980s, Korean programs in the 2000s) |

From Visitor to Seller | ||

| ↓ | (Key Tokyo-based broad-casters) |

Format and remaking International co-productions Move intro channel business |

Weak profitability | Set up individual booths at major trade fairs | Ongoing direct business with repeat customers. (However, as even this way it is impossible to achieve global coverage) subtract out to famous major agents. |

| ↓ | (Individual companies’ efforts to create brands) | (Independence from trade fairs) | |||

| ↓ | (BBC, other mega media) | Broadcasters turn into brands Development of diversified program genres into brands (individual productions don’t sell), cross-media development in the countries concerned |

Strong desire to make profits | In-house-organized trade fairs e.g. BBC showcase |

Promote via branches, subsidiaries |

of January 2016, top-class channels such as the Weather Channel, CNN, the Food Channel, and the Discovery Channel having nearly 100mn household subscribers) the service is close to the local production and consumption model.

6-5 Moves into internet distribution

In the worlds of movies and music, major US and UK companies are highly competitive and command large shares of the global market and markets in countries around the world. Domestically capitalized competitive companies may be strong in their own countries, but overseas they are presences on par with independents. However, global players in most countries are sufficiently competitive vis-a-vis the said domestically capitalized companies. These kinds of industrial organizations are also gradually forming in internet distribution business. Broadcasters have erected barriers via public regulation, but internet distribution of movies and music is a free market. In the era of broadcasting and telecom convergence, broadcasting is under pressure to consider expanding its area of business to include internet distribution. This is also the case in the UK, which is advanced in terms of overseas program sales.30

Figure 11 Global players of content-business

| Examples of global players | Domestic majors, ethnic | |

|---|---|---|

| Film | Six Hollywood majors | In most countries, American movies have the lion’s share of the market, domestic movies the second-highest share. Movies made in other countries have an independent-like presence. |

| TV | Hollywood dramas Japanese anime BBC |

As broadcasting required approval in all countries, domestic majors were protected, and compared with other industries it was difficult to achieve a global presence. |

| Music | Universal, W.B., Sony | In countries with ethnic or domestic majors, level that should be rated highly (although many countries do not have this). |

In terms of content lineup, global players such as Amazon Prime and Netflix are moving toward development of original content in addition to re-distribution of content of traditional content holders. Unfortunately, Japan appears unable to produce global players in internet distribution.

Development of overseas sales of Japanese TV programs was at one time hindered by the fact that rights to internet distribution were not included. From the perspective of buyers, it is easier to utilize acquired programs if they are sold on an “all rights,” basis, including not only broadcasting rights but also internet distribution rights and the right to use various promotional and advertising materials, etc. This is thought to have been demanded in particular in emerging countries, where there was demand to view content via the internet. However, because in Japan’s broadcast program rights the idea has been promoted of traditional terrestrial broadcasting “plus” rather than “one-chance” rights (as with movies), as regards subsequent overseas program sales, there was a need to revise rights treatment including broadcasting rights overseas (of course rights treatment of recent programs has factored in overseas program sales). From the perspective not only of the time negotiations take, but also from a creative control perspective, when consent is withheld, negotiations cannot even take place as the rights holder cannot be determined and as a result programs cannot be sold. Due to the spread of illegal distribution via the internet, even if broadcasting rights consent was issued, in most cases consent to internet distribution was withheld. In fact, in the 2000s, companies including rights organizations and broadcasters’ biggest policy requirements to government (in the government’s intellectual property planning for example) was measures to combat illegal distribution via the internet.

7. Outlook

Undoubtedly, development of overseas sales of Japanese TV programs has emerged from a phase in which the main driver was international exchange and as a business it is evolving and becoming more advanced. I think government policy helped.

However, it is hard to imagine all enterprises keeping pace with this advancement. In other words, if there are businesses still promoting this diversification, there are also businesses seeking to survive as broadcasters by securing non-broadcasting revenues in different forms. Government policy making based on these kind of differences will be an issue in the future.

As regards the commercial aspect of the sale of programs overseas, given signs that economic protectionism is likely to arise, traditional American ideology might retreat and approval of French thinking arise. What must not be forgotten is the aspect of “international cultural exchange.” The indivisible character of film and television-“is it art or commerce?”, “is it news or commerce?”-beyond the fact that film and TV production still costs money, remains indivisible. The commercial aspect of selling programs abroad has become strong within the overall flow, but it has not lost its other character aspects. Only the balance point has changed. We must ensure that it does not lose that “something else” that should be transmitted. I think creative control, which is one of the difficulties of rights treatment, will become ever more difficult and is an aspect that should never be treated lightly.

Notes

- 1 See my manuscript (2012)a for the historical overview.

- 2 Cf. JAMCO (2004)

- 3 Cf. Goro Oba (2016)

- 4 There are many arguments on both sides of the Atlantic. The issues are also debated by academics, and covering all these discussions is difficult. Against this backdrop, it is possible to obtain an overview of both sides’ ways of thinking from Hoskins et al (1997), Noam & Millonzi (1993), Dale (1997), and Finney (1996).

- 5 A system in which certain genres are shown in a limited number of cinemas. Between the wars, in 1927, at least 7.5% of films shown in UK cinemas were made in the UK. In 1935, the ratio rose to at least 20%. The proportion of locally made films shown and the time weighting of such films can be measured. In Korea and other countries, for example, “locally produced films were shown in 13 weeks out of 52” is a metric. At the WTO and other venues, the US has said that quotas are problematic as it regards them as non-tariff barriers.

- 6 In fact, expectations of this kind of ripple effect are frequently expressed in documents issued by METI’s Media and Content Industry Division in the 2000s.

- 7 Symbolically, the Berlin Film Festival started in 1951, when the Cold War was at its peak, in West Berlin, a focal point in the conflict.

- 8 Called seichi junrei (film pilgrimage) in Japanese.

- 9 According to trade statistics from the US Department of Commerce (2016 statistics, 2015 figures), film and television exports totaled USD17,789mn, while imports amounted to USD4,504mn, representing a substantial export surplus. The MPAA/MPA, in its regular report “The Economic Contribution of the Motion Picture & Television Industry to the United States,” frequently cites the industry’s contribution to creating employment and the trade balance.

- 10 It is impossible to accurately gauge Japan’s film and television trade balance as Japanese trade statistics do not include items that specify film and broadcasting. However, considering Japan’s substantial trade deficit with the US of over USD600mn (exports to the US in 2015 totaled USD7mn, while imports amounted to USD683mn), even if we take into account total exports of Japanese movies estimated by the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan (over USD110mn) and exports of TV programs released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (around USD180mn), in terms of trade balances with other countries, the amounts cannot possibly reach the levels required to offset the trade deficit with the US.

- 11 Film and television are goods/services that communicate views and ideas and carry high costs, the costs gradually decreasing. While literature and books also transmit views and ideas, they become an object of trade friction relatively rarely. An exception is the discussion at the WTO (1997) concerning imports and exports of magazines between the US and Canada, which are on the same continent and share a common language.

- 12 Cf. NHK (2003)

- 13 The rules in effect prohibited TV networks from syndication activities and from securing rights to programs. They were also designed to protect production companies, which were in a relatively weak position versus broadcasters, and aimed to expand localism together with the Prime Time Access Rule (PTAR). In the end they benefited Hollywood. They were scrapped in 1996.

- 14 According to figures for 2015, the movie industry paid special taxes of €140.3mn and received subsidies totaling €332.5mn, while broadcasters paid €504.3mn and received €289.1mn.

- 15 Specifically, investment from investment company Channel Four Films.

- 16 Cf. Puttnam (1997)

- 17 Cf. BFI website

- 18 This comprised activities aimed at securing windfall profits (rent), which arises when industrial organizations create systems that are beneficial to them in the reorganization of social systems.

- 19 Of course rules on the ethics of content and broadcasting codes can be non-tariff barriers, and all countries have something of this nature. I think these too are weaker in Japan than elsewhere. For example, as the history of anime exports shows, ethical restrictions on depictions of sex and violence have tended to be tighter overseas and weaker in Japan. There are still some doubts as to whether such regulations should be on the trade issue agenda.

- 20 Japan has concluded agreements with Canada (Common Statement of Policy on Film, Television and Video Co-production Between Japan and Canada, 20 July 1994, Tokyo) and Singapore (Common Statement of Policy on Film, Television and Video Co-production Between Japan and Singapore, 26 April, 2002, Singapore). However, both are thought to be rarely applied and are inactive. UNIJAPAN in the past exchanged memoranda with France. However, this has ended and even if it were to be revived, as France demands that Japan become a signatory to the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, the situation is difficult.

- 21 METI (2013) Trade in Services, 2012 Report on Compliance by Major Trading Partners with Trade Agreements, Part II, Chapter 11, p592, 22 April 2013.

- 22 Government Revitalization Unit “work classification”

2009, Job No. 2-57 “Content industry strengthening measures support” 26 November 2009 http://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/9283589/www.cao.go.jp/sasshin/oshirase/h-kekka/pdf/nov26kekka/2-57.pdf

2010 Job No. A-13(2) “Verification of overseas development of local content” 16 November 2010. http://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000103233.pdf - 23 Q&A at a Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan press briefing (January 2016)

- 24 http://www.gettyimages.co.jp/footage

- 25 Participants include the BBC, NHK, CX, ABC, Disney, Warner Brothers, Sky, AFP, Bloomberg, Discovery, National Geographic, and Kyodo News.

- 26 The success of sales of formats such as TBS’s Sasuke (titled Ninja Warrior in the US) are noteworthy examples alongside the success of anime when thinking about Japan’s overseas film and television sales, including success in the hard-to-break-into US, which takes considerable effort to achieve, the spread to other countries overseas and the accompanying Endemol copyright lawsuit. Cf. Makito Sugiyama (2012), TBS TV (2012)

TV Asahi Holdings and Fuji Television Network (FCC) are working on international co-productions with major partners, including remakes of dramas in China and anime in India. Cf. TV Asahi Holdings (2015) - 27 For example, see Overseas program sales consideration committee (2012), pp28-33.

- 28 http://tokyodocs.jp/

- 29 Nippon Television Network Corp. has been particularly active in this area, investing in Taiwan’s CNplus Production, Inc. (http://www.cnplus.com.tw/) and Singapore’s NTV Asia Pacific (http://www.ntvap.com/) among others.

- 30 Cf. Steemers (2014), Steemers (2016), etc.

References

- NHK (2003), Eigakai to tairitsu: katsuro o gaikoku eiga ni [Opposition to movie industry: overseas movies as a means of escape] NHK wa nani o tsutaete kita ka- NHK terebi bangumi 50 nen [What has NHK broadcast- 50 years of NHK programs] 1 February 2003

http://www.nhk.or.jp/archives/nhk50years/history/p09/ - Goro Oba (2016), Terebi bangumi no garapagoska ni wake ga aru [There is a reason for the Galapagos-ization of TV programs], http://obagoro.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-57.html(2016/04/13)

- Yoshiyuki Oshita (2009), Eikoku no kurietibu sangyo seisaku ni kan suru kekyuu [Research into the UK’s creative industry policies] Kikan seisaku – keiei kenkyuu [Quarterly policy – management reaserch] Vol. 3, 2009, pp.119-158

- Overseas program sales consideration committee ed. (2012) Terebi bangumi no kaigai hanbai gaidobukku-genjou, nohau, atarashii tenkai [TV program overseas sales guidebook-current situation, expertise, new developments] Visual Industry Promotion Organization / Maruzen 2012

- METI (2013) Saabisu boeki [Trade in Services], 2012 nen ban fukousei boeki hohkokusho [2012 Report on Compliance by Major Trading Partners with Trade Agreements] 22 April 2013

- METI’s Media and Content Industry Division Kontentsu sangyo no genjou to kadai [Content industry current situation and issues], Kontentsu no genjou to kongo no hatten no houkousei [Current situation with content and direction of future development], annual

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP) Media sofuto no seisaku oyobi ryuutsuu no jittai chousa kekka ni tsuite [Media software policy and distribution siutation survey results] (latest title), each year

- Minoru Sugaya and Tatsushiro Shukunami (ed) (2007), Toransunashionaru jidai no dejitaru kontentsu [Digital content in the trans-national age] Pub. Keio University, 2007

- Minoru Sugaya, Kiyoshi Nakamura (ed.) (2002) Eizo kontentsu sangyou ron [Film and TV content industry theory] Maruzen, 2002;

- Minoru Sugaya, Kiyoshi Nakamura (ed.) (2002) Eizo kontentsu sangyou to firumu seisaku [Film and TV content industry and film policy] Maruzen, 2009.

- Makito Sugiyama (2012) SASUKE sekai kibo de ninki futtochu! [SASKUKE popular worldwide!] saishin beiban wa gosenmannin cho shichou, shingaporuban mo daiseikou! latest US version seen by over 50mn, Singapore version also hugely successful! Ayaburo [Ayaburo] 2012/9/7 http://ayablog.com/?p=354)

- Shim Sungeun (2007) Eizo media no kokusaika nichibeiei no seisaku hikaku o chuushin ne shite [Film and TV media internationalization centered on Japan-US-UK comparison] NHK housou bunka kekyujo nenpo 2007 [NHK broadcasting culture research institute annual report 2007]

- TBS (2012) Wipeout soshou de bei ABC, Endemol USA sha to wakai ketchaku [Wipeout lawsuit ends in settlement with ABC, Endemol USA] (25 January 2012) http://www.tbs.co.jp/company/news/pdf/201201251400.pdf

- TV Asahi Holdings (2015) Terebi asahi no shin ajia senryaku! tai indo no media oute kigyou to teikei bankoku nu bizinesu biyuro kaisetsu [TV Asahi’s new Asia strategy! Tie-up with Thai and Indian media majors Opening of business bureau in Bangkok] (31 March 2015)

http://company.tv-asahi.co.jp/contents/press/0309/data/150331-asia.pdf - Cabinet Office intellectual property strategy headquarters Chiteki zaisan suishin keikaku [Intellectual property promotion plan] various years

- Japan Media Communication Center (JAMCO) (2004), Dai 13 kai JAMCO uebusaito kokusai shimpojiumu-nihon no terebi bangumi no yuushutsunyuu joukyou-2001-2 nen ICFP chousa kara [13th JAMCO website international symposium-state o Japanese program imports and exports-from 2001-2 ICFP survey], Japan Media Communication Center (JAMCO), Feb-Mar 2004

- Yumi Matsumoto and Norihiro Tanaka (2017), Nihon no bangumi kontentsu no kokusai tenkai oyobi juyou jitai ni kan suru jittai [Situation with regard to international development and reception of Japanese program content] Housou kenkyuu to chousa [Broadcasting research and survey] (NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute) January 2017 edition, 1 January 2017.

- Hirofumi Yamaguchi (2008), Kontentsu sangyou koushin no seisaku doukou to kadai [Policy trends and issues in content industry promotion] Refuarensu No. 688 [Reference No. 688], 2008.5

BFI “Channel 4 Films/Film on Four/FilmFour,” and “Channel 4 and Film” in BFI Screen Online,

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/840487/

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1304135/ - Caves, Richard E.(2000), Creative Industries: contracts between art and commerce, Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 2000, .

- Cooke,L.(1999), “British Cinema” in Nelmes, J. eds.(1999), An Introduction to Film Studies, Routledge.

- Dale, M.,(1997), The movie game, Cassel.

- Finney, A.,(1996), The state of European Cinema, Cassel

- Hoskins, C. et al.(1997), Global Television and Film ‒An Introduction to the Economics of the Business, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1997.

- Johnston,C.B.,(1992) International television co-production, Focal Press1992.

- MPAA/MPA(2016), ”The Economic Contribution of the Motion Picture & Television Industry to the United States”Feb.2016. Feb.2015, Dec.2013

- Noam, E.(1991), Television in Europe, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991.

- Noam, E. and J. C. Millonzi eds.(1993), The International Market in Film and Television Programs, Norwood: Ablex, 1993.

- Nowell-Smith, G. & S.Ricci, (1998), Hollywood and Europe, British Film Institute,

- Puttnam.D. & N. Watson,(1997) The undeclared war The struggle for control of the worlds film industry, HarperColinsPublishers, 1997.

- Steemers, J.(2004), Selling television: British television in the global market Place, London: British Film Institute, 2004.

- Steemers, J.(2014), ‘Selling Television: Addressing Transformations in the International Distribution of Television Content,’ “Media Industries Journal”1.1 (2014)

- Steemers, J.(2016), ‘International Sales of U.K. Television Content: Change and Continuity in “the space in between” Production and Consumption’, “Television & New Media”, 2016, Vol. 17(8) 734–753.

- Manuscript (2007), Jyapan kontentsu no kaigai hasshin-eizou to jouhou no kokusai bijinesu ryuutsuu kouzou [Overseas transmission of Japanese content-international business distribution structure of film and television and information] Jouhou tsuushin gakkaishi [Information distribution study group magazine] Vo. 25 No. 1, 2007.5

- Manuscript (2012)a, Wagakuni no houshou bangumi kaigai hanbai to sekai no bangumi toukei ni kan suru genjou [Overseas sales of Japanese programs and global program statistics] Jouhou tsuushin seisaku rebiyu [Information and communication policy review] Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP), No. 5 (28 September 2012)

- Manuscript (2012)b, Wagakuni kontentsu sangyou no kaigai tenkai [Overseas development of Japan’s content industry], Sougou chousa [Survey] Gijutsu to bunka ni yoru nihon no saisei [Regeneration of Japan via technology and culture] (National Diet Library), pp119-137.

*Links are for posted items. It is possible that some items are not currently available or are being edited.

Takashi Uchiyama

Professor of Policy Studies, Graduate School of Cultural and Creative Studies, Aoyama Gakuin University

Specializes in film and television content industry management strategy and government economic policy.

1994 Gakushuuin University graduate school management studies graduate course doctorate second half curriculum full period left the university,

Researcher, the Japan Commercial Broadcasters Association Research Institute,

special senior researcher, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) Institute for Information and Communications Policy (IICP), etc.

Return to 25th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 25th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page