21st JAMCO Online International Symposium

March 14 to September 15, 2013

Tsunami Response Systems and the Role of Asia's Broadcasters

Tsunami Disaster Prevention and the Roles of Media in Thailand

A tsunami is capable of destruction in a particular geographic region, generally within about 1,000 km of its source. A regional tsunami occasionally have very limited and localized effects outside of a specific region. Most of the destructive tsunami can be classified as local or regional, meaning their destructive effects are confined to coasts within a hundred km, or up to a thousand km, respectively, of the source(*1).

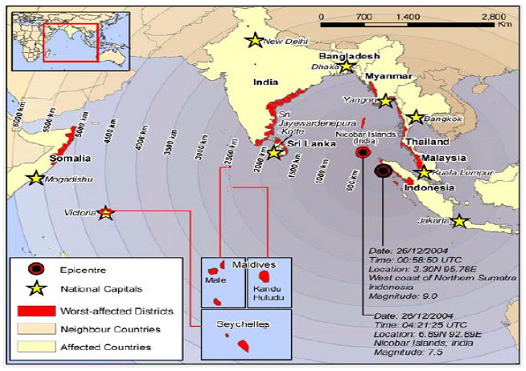

In the early morning of Sunday, December 26, 2004, a giant undersea earthquake created a tsunami with an epicenter off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The first tsunami surges arrived at the closest land only eight minutes after the earthquake. It took 15 minutes for the first waves to hit northern Sumatra and about two hours to reach Sri Lanka and Thailand. This catastrophe took over 200,000 lives from 12 countries (Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand) around the Indian Ocean (Figure 1), leaving 2.3 million people homeless.

Few people along the coastlines of the Indian Ocean were aware of tsunami and their natural warning signs(*2). And there was no tsunami warning system to warn people who were far from the origin of the impending waves(*3).

Figure 1: Twelve Countries Affected by the 2004 Tsunami

(Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, in Indian Ocean Earthquake

and Tsunami: Humanitarian Assistance and Relief Operations, CRS Report for Congress (2005).

)

(Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, in Indian Ocean Earthquake

and Tsunami: Humanitarian Assistance and Relief Operations, CRS Report for Congress (2005).

)*1 USAID (2007) Tsunami Warning Center Reference Guide, U.S. Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System Program (US IOTWS), Bangkok.

*2 A rapid surging of the ocean waves which is similar to an extremely powerful river or flood. The approaching tsunami sounds like three freight trains or the roar of a jet. In several places the tsunami announced itself in the form of a rapidly receding ocean before advancing as a torrent of foaming water. Many reports quoted survivors as saying that they had never seen the sea withdraw such a distance, exposing seafloor never viewed before, stranding fish and boats on the sand., Tsunami Smart, 2010.

*3 Humboldt Earthquake Education (2011) Living on Shaky Ground: How to Survive Earthquakes and Tsunami in Northern California, Part of the Putting Down Roots in Earthquake Country Series.

Structure of the Report

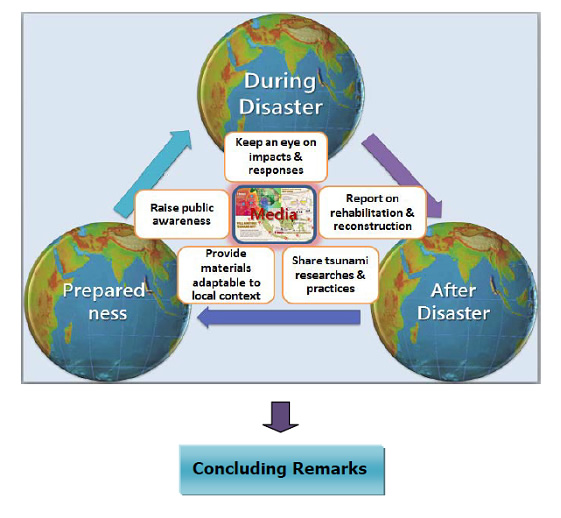

This report is organized as follows. First, the impact of the 2004 tsunami on Thailand is described, followed by the emergency reactions/responses, called ‘during disaster’. Second, rehabilitation and reconstruction are discussed in the ‘after disaster’. Section Third, preventing and mitigating disasters from the unexpected recurrence of tsunami, ‘preparedness’, is examined. In each respective heading mentioned above, Figure 2 shows the roles of media that the broadcasters in Thailand have been playing so far to ameliorate this kind of situation, to mitigate and prevent such damages. Finally, an effective form of international cooperation among countries prone to tsunami, which provides a great lesson on how to mitigate devastating disasters and prevent the loss of life, is described in the concluding remarks.

Figure 2: The Roles of Media in the 2004 Tsunami Disaster

Source: Compiled by author

Source: Compiled by authorDuring Disaster: Impacts and Responses

The events of the 2004 tsunami disaster occurred in the following chronological order.

Table 1: Critical Tsunami Events on December 26, 2004(*4)

Figure 3.1: Areas of Thailand Affected by the 2004 Tsunami

Source: www.mapsofworld.com

Source: www.mapsofworld.comThere were two types of affected areas: the first type was softly hit by the earthquake, which was felt by people but did not cause any damage to buildings, properties or lives. Provinces affected were Bangkok (only high buildings), the capital of Thailand, which is located in the central region, and Chiangmai, Chiangrai, Mae Hongsorn and Lampang, located in the northern region.

The second type received severe damages. These provinces are located along the west coast, in the southern part of Thailand(Andaman Sea), consisting of Krabi, Trang, Phang-Nga, Phuket, Ranong and Satun.

Thailand experienced enormous damage, even though the earthquake occurred nearly one and a half hour before the tsunami hit the country. This is because nobody had had experience with tsunami; most of the people didn’t know what a tsunami was.

*4 Ministry of Culture (2005) Events of Disaster Tsunami: 26 December 2004, the Anniversary of Tsunami Disaster.

*5 This radio frequency is owned by The Royal Thai Government and rented out to private company in 1991. It mainly reports daily news and traffic situations in Bangkok and the vicinity.

*6 This is a state television Channel, operated by the Public Relations Department, the Office of the Prime Minister. For further information, please access www.prd.or.th.

*7 Thirakul, Viroj (2005) Fencing Tsunami Off!: Operation of the Century, Business.Com, Bangkok,p.150.

*8 This is a radio station leased out by the government. It mainly reports news like a news station. Its radio frequency is 97.0 MHz., covering Bangkok and the vicinity.

*9 Ministry of Culture (2005) Events of Tsunami Disaster: 26 December 2004, the Anniversary of Tsunami Disaster, p. 50.

*10 ITV (Independent Television) was established in 1996 and went out of business in 2007.

*11 The Mass Communication Organization of Thailand (MCOT), established in 1977, is known as TV Channel 9, or Modern nine Television.

Remarks on Day One

-

There were only two government agencies, DMR and TMD, through which the media could have access to tsunami news.

-

TMD reported the quake (the first official tsunami announcement *12) at 09.00 hr. on December 26, 2004. But the news was aired at 09.20 hr., which was not pertinent to the Radio Thailand Station’s news time (State Radio News), which is usually broadcast nationwide at 07.00, 12.00 and 19.00 hr.

-

TMD officials attempted to acquire more information directly from Indonesia through the Website http://www.embassyofindonesia.org/. The head of the division responsible for this matter and officials concerned rushed to TMD and helped contact meteorological agencies and disaster agencies, both domestic and international, while a great number of people kept on asking for detailed information.

-

In issuing an official risk warning, the issuer must be very prudent, since tsunami had never occurred in the Indian Ocean. Obviously, this giant tsunami was much beyond the usual expectation(*13).

-

The first tsunami announcement was aired by FM 100 Radio Station and later by GG News Radio Station which are general radio news stations and the radius of operation covers only Bangkok and vicinity, not nationwide. This means that the 2004 tsunami event initially was considered as common news.

-

In 2004, Thailand had six free Television channels, which were based on commercial practice (advertising): channels 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and ITV (Independent Television). As such, the time schedule had been routinely allocated to program organizers and sponsors. Time used for breaking news, such as the tsunami, would affect the scheduled program. (Later in 2008, a public television station with no commercial advertising, Thai PBS, was established.) The rest were satellite cable TV and IPTV(Internet Protocol Television).

-

In 2004, all radio stations in Thailand were owned by the state. Private entities had to rent time slots from government agencies in charge. The network stations could run their own broadcast news/programs, but they had to link and broadcast daily national news programs from Bangkok (Public Relations Department) at 7.00, 12.00, and 19.00 hr. Therefore, the tsunami official warning at 9.00 hr. was not pertinent to the national news time.

-

After the 09.20 warning, there was no statement regarding disaster prevention or evacuation, but only “at this early stage there were no losses reported”. As so, during 08.00-09.30 hr., there was no serious warning at all until the tsunami hit the west coast of Thailand.

-

TV Channel 11 in Phuket(*14) went on air immediately after the big waves struck Phuket Island. Pictures on television screens called for government’s quick responses, appealing for the public’s understanding. The TV station broadcasted images of the tsunami and its aftermath. The station was transformed into an action center, providing not only news and information, but also temporary shelter for foreign tourists affected by the tsunami. The station provided the link between the public and relief agencies(*15).

It can be seen that the media broadcast only the information supplied by the government officials from the agencies responsible for reporting the crisis. As shown, their reactions indicate flaws or deficiencies in the media in dealing with this devastating tsunami. The role of media to minimize losses was very little, since they did not know anything about tsunami. They could not tell people what to do and how to protect themselves when the tsunami hit Thailand.

During the first day, media focused more on broadcasting the sensational scenes (such as devastating damages) rather than providing information about the tsunami and its risks. Lacking tsunami knowledge, media could not efficiently warn about the disasters. They were inclined to believe official opinions rather than finding facts by themselves(*16).

After the first day, media learned more and realized the severity of the situation. The mass media played a very significant role in reporting and updating the public on the aftermath of the disaster. They also informed the public what assistance was urgently needed at which places and times. Donations solidified and were transferred to the needy.

To summarize the main events later on, the following impacts and responses were reported by the media (Table2).

Table 2: Impacts and Responses to the Tsunami Disaster in Thailand(*17)

The impacts of the 2004 tsunami on Thailand were most severe on the Andaman Coast, devastating six provinces: Krabi, Phang Nga, Phuket, Ranong, Satun, and Trang. The damage and loss of lives were very large. For example, there was a large number of affected areas (407 villages, 95 sub-districts and 25 districts); 7,195 small fishing boats were destroyed; 6,764 families lost their fishing gears: and 7,487 families lost their aquaculture livelihood. It also resulted in 30,000 million baht of loss to the tourist industry along the Andaman coast areas. Many lives could have been saved if there had been an effective tsunami warning system. The tsunami exposed major flaws in Thailand’s hazard management and emergency response systems. The media could play a greater role thereafter in bringing all parties to build and upgrade effective crisis management system.

*12 There were only two government officers at TMD on Saturday night December 25, 2004. Having learned about the giant earthquake, they reported to higher ranking officers until the first official announcement was issued.

*13 The Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) was established in 1986 at the initiative of the then UN Disaster Relief Organization, now known as the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, with the aim of strengthening national disaster risk management systems in the region. Relative risks of hazards, vulnerability, level of management and disaster occurrence in Thailand were examined by ADPC in the 1994 study “Strengthened Disaster Management Strategies in Thailand” which concluded that earthquakes in Thailand in terms of hazard and vulnerability were low, but was poor in management and moderate in disaster risk, while regional or distant tsunami had not yet been included in the list. Since then, tsunami and other risks (avian flu, SARS, terrorism, climate change, etc) have been added to the list of risks of Thailand.

*14 The local station of the TV Channel 11 network located in Phuket province.

*15 Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) (2005) in The Tsunami’s Wake: Media and the Coverage of Disasters in Asia, by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and the Southeast Asian Press Alliance, 28-29 April 2005, Royal Phuket City Hotel, Phuket.

*16 Knight, Alan (2006) Covering Disaster and the Media Mandate: The 2004 Tsunami, Asia and Asian Communication Quarterly. Vol. 33, No. 1 & 2, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

*17 Excerpted from a paper Rak Thai and World Vision Reports, prepared by Danai Sundhagul, Multi-agency Joint After Action Review, Bangkok, April; Proceedings, UNDAC Mission Report; Dec. 28 to Jan. 12, 2005, referred to in A. Mashni and Associates (2005).

*18 Figures on the dead and missing vary with the source. As of April 19, 2005 the Thai Ministry of Interior, Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation estimated 5,395 dead (1,961 Thai, 1,953 foreigners and 1,481 unidentified) and 2,845 missing (A. Mashni and Associates, 2005).

*19 Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (2010) Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction 2010–2019, Ministry of Interior.

After Disaster: Rehabilitation and Reconstruction

Rehabilitation and reconstruction are the main tasks of after-tsunami efforts. The Thai government and many international donor communities focused on priorities in supplying consumable items needed for immediate use (food, clothes, shelter, and medicine), followed by small and medium-sized housing and infrastructure projects. The provision of items of this kind is extremely helpful and media also play a great role in this regard. The broader issues of long-term sustainability of survivors, especially local people, however, receive less attention under these types of programs. So, it is up to the local communities themselves in the tsunami-affected areas to tackle the difficult issues of long-term sustainable development(*20).

Beside the issues already mentioned, mental health issues were obvious, ranging from anxiety to severe depression. Livelihood recovery was the highest priority, especially programs that helped restart income-generating activities. Rights of minorities, IDPs (Internally Displaced Persons), vulnerable people and land rights issues were serious concerns, as they imposed barriers to reconstruction of permanent shelters. Some Thai IDPs faced total loss of their lands to tourism investors.

Local and international media played a key role in helping claim-holders acquire equal access to tsunami assistance and advocating for indigenous people’s rights in land disputes(*21).This is because the land (coastal areas) affected by the tsunami that used to be occupied by local people (with or without legal rights) had now become open land(*22). Investors and influential people aimed to get such “gold coast” areas to build resorts, hotels, casinos and shrimp farms. All they had to do were to stop local people coming back to their old villages, so they used their influence to get higher politicians and authorities to agree to their schemes. This issue was raised by NGOs and volunteers through the media when they helped local people to reclaim their rights, whereas the government decided to use this opportunity (the aftermath of the tsunami) to regulate land use planning and building codes and regulations in the affected land. A key government strategy in all six provinces was to relocate local people without legal land tenure to public sites where tenure was based on long-term, low-rate rented housing. Hence, land disputes have been at the core of many recovery and reconstruction efforts.

The Thai government officially announced the December 26 of every year to be ‘National Disaster Prevention Day’ in order to warn the public and remember the devastating 2004 tsunami. Even though, journalists, broadcasters, etc. are eager to report tsunami news during this time, the content mostly focuses on preparedness of the tsunami early warning system, while the issues raised above remain to be solved and have gradually disappeared from the media.

*20 A. Mashni, S. Reed, V. Sasmitawidjaja, D. Sundhagul and T. Wright (2005) Multi-Agency Evaluation of Tsunami Response: Thailand and Indonesia, CARE International, World Vision, August.

*21 E. Scheper (2006) Impact of the Tsunami Response on Local and National Capacities, Tsunami Evaluation Coalition, Thailand Country Report, TEC April, 2006.

*22 Documents for claiming legal rights to land were lost in the tsunami.

Preparedness: The Next Tsunami

Before the 2004 tsunami, natural disaster warning agencies in Thailand had a problem in communicating with the public. There have been at least three government agencies (TMD, DDPM and DMR) directly responsible for natural disaster warning, but they were unlikely to issue official warning statements until they were sure that hazards really occurred. Of course, there have been official warnings when it was visible, for example, in the case of a typhoon. But if it is invisible, for example, the forecast of a storm surge or tsunami, and if a warning is issued but nothing occurs, the business community (i.e. tourism) would complain that such warning signals had negative impacts on their businesses. This makes it difficult to promptly disseminate panic information. Even though there is a warning context appearing in the official statement, it seems too generic or broad and often full of technical terms, so it is not easy for public to understand.

After the 2004 tsunami disaster, more attention has been paid to disaster preparedness, focusing on disaster risk reduction efforts, coupled with generating awareness at the community level. This can be observed from policy, legal and institutional changes that provide the basis for risk reduction. These have been improved, enacted and translated into practice.

Thailand set up the National Disaster Warning Center (NDWC) on May 30, 2005, affiliated with the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, to be the coordinator of inter-ministerial organizations that issue early disaster warning announcements. The Master Plan on Tsunami Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (2009–2013) and the Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction (2010–2019), written by the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (DDPM), Ministry of Interior, have been implemented so far and involve many agencies(*23). To be effective, the government set up the National Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Committee. Its key role is to integrate and develop the disaster prevention and mitigation plan of government agencies, local government agencies and private agencies (Table 3).

Table 3: National Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Committee and Its Roles

Source: Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction (2010–2019), Diagram 10.1.1, p.9

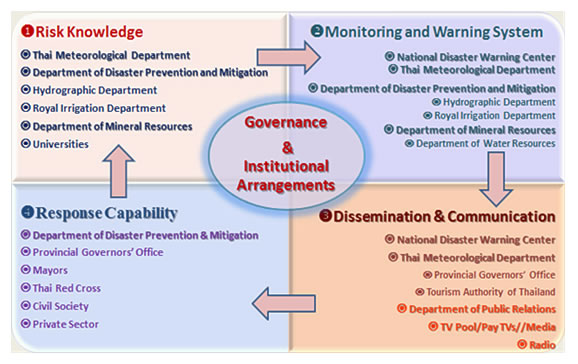

Source: Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction (2010–2019), Diagram 10.1.1, p.9In 2009, UNDP reviewed Thailand’s institutional and legislative arrangements and policy related to disasters. The discussion focused on four main areas, presented in Figure 4 which aimed at enhancing the effective, community or people-centered early warning system (EWS *24). These are (1) governance and institutional arrangements, (2) risk knowledge, (3) monitoring and warning system, (4) dissemination and communication, and (5) response capacity.

Figure 4: Institutional Roles and Responsibility in the Thailand EWS(*25)

In each of the four areas, there is involvement with many parties in both the public and private sector. The media, in order to disseminate and communicate EWS well and effectively to the public, have to learn risk knowledge, response capacity, monitoring and warning systems. This means the media has to have a good relationship with the organizations indicated in Figure 4.

*23 The administrative system in Thailand is divided into three levels: central, provincial and local. The Ministry of Interior along with its hierarchical agencies is the core of administration along this line of command from the center to the localities.

*24 Attention has been devoted to community-based or ‘people centered’ systems. The Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (DDPM) and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) jointly present these “Guidelines for Field Practitioners to Implement the Community-Based Disaster Risk Management in Thailand: CBDRM” in the Thai language. DDPM and GTZ began to implement them soon after the disastrous tsunami of December 2004. This document has been published in order to be applied as groundwork for all further training of field practitioners and the implementation of CBDRM as scheduled for 2007 onwards (Nilubon Supanich, 2006).

*25 UNDP (2009) Institutional and Legislative Systems for Early Warning and Disaster Risk Reduction: Thailand, Regional Program on Capacity Building for Sustainable Recovery and Risk Reduction.

Thai Media’s Questions about Information Needs

There have been many issues raised and points made in the past by Thai media during the workshop Launching the Framework and Communication Technology and Methodology, in the U.S.-Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (US IOTWS) Program, Proceedings of Tsunami Alert Rapid Notifications System (TARNS). Different media experts explained how they have received information during the times of disaster and what they do afterwards. The following are issues and concerns raised by media(*26) after the 2004 tsunami ,when a newly established NDWC (in 2005) was not yet fully-fledged functioning.

-

When a TV channel receives any information, they try to crosscheck it with other agencies, as well as with the affected community, before announcing the news. In most cases, the media call NDWC through its call center number, but they sometimes are unable to get through.

-

The media do not fully trust NDWC’s information. Most of the time, the media rely on information from TMD.

-

Whenever NDWC sends a fax to the media, they double check with other news outlets for accurate information, as NDWC had been newly established. The media did not yet have a strong relationship with NDWC. However, NDWC’s reliability is increasing.

-

Some media do not know what NDWC’s role is, where it is located, or what the call center number is. For example, during the last Indonesian tsunami, they called the former Director General of TMD and got some information, instead of contacting any NDWC staff.

-

TV Channel 5 has a secure and close relationship with NDWC. On behalf of Channel 5, a representative proposed that the media should develop good partnership with NDWC.

-

TV Channel 11 Phuket so far has worked closely with agencies involved with disasters: NDWC, DDPM, and TMD, as well as the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC).

*26 USAID (2006) Launching the Framework and Communication Technology and Methodology, Second Workshop, Proceedings of Tsunami Alert Rapid Notifications System (TARNS), U.S.-Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (US IOTWS) Program.

Aceh Earthquake and Tsunami Warning in Thailand on April 11, 2012

An earthquake measuring 8.9 on the Richter scale struck at 15.38 hr. on April 11, 2012 near Sumatra, Indonesia, which was followed by aftershocks measuring up to 8.8 on the Richter scale. The quake was centered 20 miles beneath the ocean floor about 270 miles from Aceh’s provincial capital. The tremor was felt in Singapore, Thailand, Bangladesh, India and Malaysia, where tall office buildings shook for more than a minute. The tsunami alert was terrifying for people who still had fresh memories of the 2004 tsunami. People in beaches in Banda Aceh, Indonesia were crying, and everybody was running inland as fast as they could.

This prompted NDWC in Thailand to issue a tsunami warning and an evacuation order for people located on the Andaman coast in southern provinces (Krabi, Phang Nga, Phuket, Ranong , Satun, and Trang) telling them to move to higher ground as a safety precaution. Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra held an emergency meeting with all relevant agencies. The media reported news and events closely.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Pacific Tsunami Warning Center said, “A significant tsunami was generated by this earthquake; at its highest waves rose 3.5 feet. The nature of the quake made it less likely for a tsunami to be generated because the earth moved horizontally, rather than vertically, and therefore had not displaced large volumes of water. In Thailand, the Information and Communication Technology minister said that the tsunami wave was only about 10 centimeters high, and did not cause any damage, so the situation had normalized.(*27) NDWC decided to lift its tsunami warning and evacuation order at 20.45 hr on the same day.

*27 www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/11

Tsunami Warning System in Thailand

The development of the Early Warning Systems (EWS) in Thailand has received an exceptional amount of attention and resources in the aftermath of the December 26, 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami disaster. A lot of emphasis has been placed upon technical and instrumental arrangements, with assistance and close cooperation with many developed countries in providing expertise and experiences(*28).

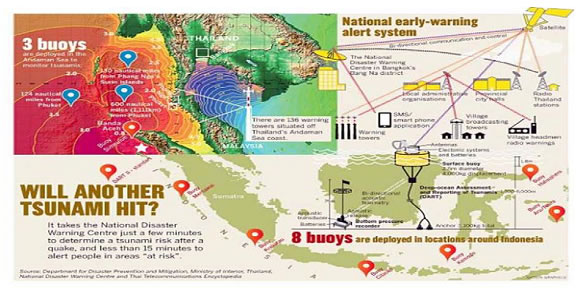

The satellite-based National Disaster Early Warning System (Figure 5) had been set up in Thailand. Indeed, this was the first time in Thailand’s history that a disaster warning system had been set up in the kingdom. The system triggers simultaneous disaster alerts through radio stations, coastal warning towers and the country’s mobile phone network. A key element of Thailand’s disaster preparedness strategy is to promote greater public awareness of the risks of various types of disasters. Mass media, therefore, play a crucial role in delivering risk knowledge and risk warning issuing from the main sources, especially NDWC. Thailand’s disaster early warning system is also helpful to other countries in the Indian Ocean region. Having learnt this lesson, the disaster warning system will be able to issue simultaneous alerts to Thailand’s radio and television stations, mobile phone networks and tsunami warning towers located in at-risk areas where a tsunami can strike.

Figure 6 illustrates domestic agencies, especially TMD, and international agencies: Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii, Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and Deep Ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) in the Andaman Sea which provide relevant earthquake (EQ) and tsunami (T) information to the NDWC, Thailand via multi data transmission modes: fax, phone, email, hotline, websites and satellite. The information obtained is processed and analyzed within 5-10 minutes before a decision is made about the degree of official warnings or lifting such warnings.

Figure 5: National Early Warning System in Thailand

Source: C. Saengpassa and P. Sarnsamak (2012) Tsunami Warning System Finally Ready, After 8 Years, The Nation, December 25, 2012.

Source: C. Saengpassa and P. Sarnsamak (2012) Tsunami Warning System Finally Ready, After 8 Years, The Nation, December 25, 2012.Figure 6: Tsunami Warning System in Thailand

Source: Preparedness for Earthquake and Tsunami in Thailand presented in the DDPM’s Website: http://www.disaster.go.th/

Source: Preparedness for Earthquake and Tsunami in Thailand presented in the DDPM’s Website: http://www.disaster.go.th/*28 Besides international organizations: UNESCO/UNDP (2009), ESCAP (2009), for example, U.S. (USAID: 2006, 2007), Norway (NGI: 2006), Sweden (SEI: 2009) and Japan had contributed technical aids with regard to EWS to Thailand.

Lessons Learned: Thai-Japanese Media

On March 11, 2011, at 14:46 hr, the Great East Japan Earthquake caused damage to Japan ranging from Hokkaido to Kanagawa Prefecture: 15,800 people lost their lives; 128,500 buildings were totally destroyed; 240,000 buildings were badly damaged and 330,000 people had to live as evacuees.(*29) Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan stated, “In the 65 years after the end of World War II, this is the toughest and the most difficult crisis for Japan.”(*30)

To handle the situation, broadcasters played a very important role. Japan’s national public broadcasters, NHK, and Japan Satellite Television suspended their usual programs to provide ongoing coverage of the situation. Other nationwide Japanese TV networks also broadcasted uninterrupted coverage of the disaster. Ustream Asia broadcasted live programs from NHK, Tokyo Broadcasting System, Fuji TV, TV Asahi, TV Kanagawa, and CNN on the Internet starting on 12 March 2011. YokosoNews, an Internet webcast in Japan, dedicated its broadcast to the latest news gathered from Japanese news stations, translating them in real time to English. All warnings were broadcasted by NHK in five languages: Japanese, English, Mandarin, Korean and Portuguese (Japan has small Chinese, Korean and Brazilian populations). It was noted that the Japanese news media has been at times overly cautious to avoid panic and often relied on confusing statements by experts and officials.

During the 2004 tsunami in Thailand, the people and the media knew nothing about tsunami. The disastrous season flood in Thailand from July to December 2011 created a panic among the public and the media. However, the media, especially TPBS (Thai Public Broadcasting Services, established in 2008), devoted its airtime to monitoring the flood situation based on its own fact-finding until the crisis had passed. Lessons learned from the damage caused by the tsunami in 2004 and preventive measures will help media better handle future disasters.

*29 https://www.jamco.or.jp/2012_symposium/en/Accessed on December 10, 2012.

*30 http://www.irfnews.org/news-events/news-detail/ Accessed on March 12, 2013.

Concluding Remarks

The 2004 tsunami accelerated efforts in the international ocean science community to cooperate and work on understanding tsunamis, their geological causes, and their impacts on coastal regions(*31). This devastating tsunami has prompted countries around the world, including Thailand, to reassess tsunami risks to the coastal communities and to develop responsive strategies for future events.

The progress has been made in disaster risk reduction (DRR) and early warning system (EWS) development in Thailand. National efforts to develop EWS initially were undertaken in the context of the establishment of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (IOTWS) initiated at the World Conference for Disaster Reduction in 2005 under the leadership of the United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organization Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO/IOC), and further international cooperation had made Thailand’s EWS fully-fledged and functional.

In 2008, the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), in consultations with regional stakeholders and partners, claimed that despite the actions taken so far, there was, amongst policy makers and practitioners at both the international and regional levels, a widespread sense of a lack of implementation on the mainstreaming of DRR as promoted under the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA)(*32). HFA urged all countries to make major efforts to reduce their disaster risk by 2015. As the evidence shows, Thailand has paid considerably more attention than before to disaster management planning and implementation.

*31 Di Jin and Jian Lin (2011) Managing Tsunamis through Early Warning Systems: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Elsevier, Ocean & Coastal Management 54: 189-199.

*32 Early Warning Subcommittee of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on International Cooperation for Disaster Reduction (2006) Japan’s Natural Disaster Early Warning Systems and International Cooperative Efforts, Government of Japan, March.

Appendix A: List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

-

ADPC: Asian Disaster Preparedness Center

-

CBDRM: Community-Based Disaster Risk Management

-

DART: Deep Ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami

-

DDPM: Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation

-

DMR: Department of Mineral Resources

-

DRM: Disaster Risk Management

-

DRR: Disaster Risk Reduction

-

EWS: Early Warning System

-

FES: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

-

FTP: File Transfer Protocol

-

HFA: Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015

-

ICG: Intergovernmental Coordination Group

-

ICG/ITSU: International Coordination Group for the Tsunami Warning System in the Pacific

-

IDPs: Internally Displaced Persons

-

IOTWS: Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System

-

JMA: Japan Meteorological Agency

-

MoPH: Ministry of Public Health

-

NGI: Norwegian Geotechnical Institute

-

NDWC: National Disaster Warning Centre

-

NGO Non-governmental organization

-

NOAA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (United States)

-

PTWC: Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

-

Raks: Thai Rak Thai Foundation

-

SEI: Stockholm Environment Institute

-

SOP: Standard Operating Procedure

-

SEAPA: Southeast Asian Press Alliance

-

TMD: Thai Meteorological Department

-

UNDAC: United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination

-

(UN)OCHA: Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

-

UNDP: United Nations Development Program

-

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

-

UNESCO/IOC: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization,/Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

-

UNFPA: United Nations Population Fund

-

UN/ISDR: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction

-

USAID: United States Agency for International Development

-

WV: World Vision

Appendix B: Mass Media in Thailand

There are six free television channels in Thailand: TV Channel 3 supervised by the authority of TV Channel 9; TV Channel 5, operated by the Royal Thai Army; TV Channel 7, owned by the Royal Thai Army and rented out to Bangkok Broadcasting & Television Company Limited; TV Channel 9, privatized under the State Enterprise Corporatization Act; TV Channel 11 established by the government to promote education and public relations campaigns for the state; and Thai PBS, the first public service broadcasting television station. Beside these, there are many satellite channels and IPTV (Internet Protocol Television).

As for radio and printed media, there are about 550 radio stations conceded or governed by the government. Most radio stations were conceded under two-year contracts for commercial purposes. There are about 6,000 community radio stations all over Thailand. Printed media, such as newspapers and magazines are quite independent and operated by the private sector.

Bibliography

-

Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA), University of the West Indies Seismic Research Centre and USAID (2010) Tsunami and Other Coastal Hazards Information Kit for the Caribbean Media, Tsunami Smart, Tsunami and Other Coastal Hazards Warning System Project.

-

Committee on the Review of the Tsunami Warning and Forecast System and Overview of the Nation’s Tsunami Preparedness (2010) Tsunami Warning and Preparedness: An Assessment of the U.S. Tsunami Program and the Nation’s Preparedness Efforts, Prepublication Copy, National Research Council, National Academies Press. http://dels.nas.edu/osb

-

Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (2010) Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction 2010–2019, Ministry of Interior.

-

Di Jin and Jian Lin (2011) Managing Tsunamis through Early Warning Systems: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Ocean & Coastal Management, http://www.whoi.edu/fileserver.do?id= ELSEVIER, 75463&pt=2&p=68128, accessed on December 27, 2012.

-

Early Warning Subcommittee of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on International Cooperation for Disaster Reduction (2006) Japan’s Natural Disaster Early Warning Systems and International Cooperative Efforts, Government of Japan, March.

-

Economic and Social Committee for Asia and the Pacific (2009) Tsunami Early Warning System in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia, Report on Regional Unmet Needs, United Nations.

-

Government of Japan (March 2006), Japan’s Natural Disaster Early Warning Systems and International Cooperative Efforts Early Warning Subcommittee of the Inter-Ministerial on International Cooperation for Disaster Reduction,

-

Humboldt Earthquake Education (2011) Living on Shaky Ground: How to Survive Earthquakes and Tsunamis in Northern California, Part of the Putting Down Roots in Earthquake Country Series. http://humboldt.edu/shakyground/

-

Knight, Alan (2006) Covering Disaster and the Media Mandate The 2004 Tsunami, Media, Asia and Asian Communication Quarterly. Vol. 33, No. 1 & 2., Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (2010)

-

Mashni, A., S. Reed, V. Sasmitawidjaja, D. Sundhagul and T. Wright (2005) Multi-Agency Evaluation of Tsunami Response: Thailand and Indonesia, CARE International, World Vision, August.

-

Ministry of Culture (2005) Events of Tsunami Disaster: 26 December 2004, the Anniversary of Tsunami Disaster.

-

Ministry of Interior. Strategic National Action Plan (SNAP) on Disaster Risk Reduction 2010–2019.

-

Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (2006) Tsunami Risk Mitigation Strategy for Thailand http://www.ngi.no

-

Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (2006) Tsunami Risk Mitigation Measures with Focus on Land Use and Rehabilitation, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.ngi.no

-

Margesson, Rhoda (2005) Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami: Humanitarian Assistance and Relief Operations, CRS Report for Congress, Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Updated February 10, 2005.

-

Saengpassa, Chularat, and Pongphon Sarnsamak (2012) Tsunami Warning System Finally Ready, After 8 Years, The Nation, December 25, 2012.

-

Scheper, E. (2006) Impact of the Tsunami Response on Local and National Capacities, Tsunami Evaluation Coalition, Thailand Country Report, TEC April, 2006.

-

Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) and the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) (2005) in the Tsunami’s Wake: Media and the Coverage of Disasters in Asia, by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and the Southeast Asian Press Alliance, 28-29 April 2005, Royal Phuket City Hotel, Phuket.

-

Supanich, Nilubon (2006) Guidelines for Field Practitioners to Implement the Community-Based Disaster Risk Management in Thailand: CBDRM, DDPM, supported by GTZ and ADPC, 24 November 2006.

-

Thirakul, Viroj (2005) Fencing Tsunami Off!: Operation of the Century, Business.Com, Bangkok.

-

Thomalla F., C. Metusela, S. Naruchaikusol, R. K. Larsen, C. Tepa(2009)Disaster Risk Reduction and Tsunami Early Warning Systems in Thailand: a case study on Krabi Province, Project Report, Stockholm Environment Institute.

-

United Nations Development Program(2009)Institutional and Legislative Systems for Early Warning and Disaster Risk Reduction: Thailand, Regional Program on Capacity Building for Sustainable Recovery and Risk Reduction.

-

USAID(2006)Launching the Framework and Communication Technology and Methodology, Second Workshop, Proceedings of Tsunami Alert Rapid Notifications System (TARNS), U.S.-Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (US IOTWS) Program.

-

USAID(2006)Proceedings of Tsunami Alert Rapid Notifications System 22 (TARNS), Second Workshop: Launching the Framework and Communication Technology and Methodology, U.S. Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (US IOTWS) Program

-

USAID(2007)Tsunami Warning Center Reference Guide, U.S. Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System Program (US IOTWS), Bangkok.

-

Weber, K.E.(2005)Tsunami 2004: Nam Chai Thai, National Identity Board.

-

http://www.dmr.go.th/ accessed on January 25, 2013

-

http://www.disaster.go.th/ accessed on January 25, 2013

-

https://www.jamco.or.jp/2012_symposium/en/ Accessed on December 2012

-

http://www.ndwc.go.th/ accessed on January 12, 2013

-

http://www.irfnewsorg/news-events/news-detail/ Accessed on March 12, 2013.

-

http://www.tmd.go.th/ accessed on January 29, 2013

*Links are for posted items. It is possible that some items are not currently available or are being edited.

Supanee Nitsmer

Assistant Professor, Ramkhamhaeng University, Bangkok

B.A. (First Class Honors in Education) 1978, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. Cert. in Graphic Reproduction, 1983, Singapore (Colombo Plan). M.A. (Mass Communication) 1991, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand. Cert. in Television Program Production, 1992, NHK-Communication Training Center, Japanese Foundation (JICA). Cert. in Television Program Production, 1995, Capilano College, Victoria, Canada (Canadian Foundation).

Work Experience:

Head of the project (1995-2005) "Youth Television Program Production," jointly organized by the Mass Communication Department of Ramkhamhaeng University and TV Channel 5, Thailand (produced youth TV program and broadcasted on TV Channel 5). Co-authors in The Appropriate Post Rating for Television Program: A Case Study of Thai TV Channel 7, Research Working Paper, 2008. Head of the Mass Communication Department (2009-2011) and Director of Graduate Studies, Faculty of Mass Communication (2012-present). Lecturer in Television Script Writing, Introduction to Journalism, and Photojournalism.

Return to 21st JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 21st JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page