28th JAMCO Online International Symposium

February 2020 - March 2020

Educational Content in the Developing Countries : Its Role and New Possibilities

Visual Media and Education in Palestine Respecting Diversity

This paper considers visual media, how it is being used and how it could be harnessed in order to achieve the desire of the Palestinian National Authority for education that respects the diversity of children. It considers the distinguishing features of and prospects for such media use. The Palestinian National Authority, the self-governing body established in 1994, shall hereinafter be referred to as Palestine.

As a region affected by conflict, Palestine is fraught with political peculiarities and fragilities that make school education complicated and arduous. The hardening of Israel’s occupation policies since the 2000 Intifada, with the restrictions imposed on the movement of people and goods by the separation barrier and checkpoints, and the constant armed strikes and repression meted out by Israeli troops in the self-governing Palestinian areas, have brought economic and emotional hardship to Palestinians. They live in unrelenting tension.

Although it has numerous issues to address, Palestine puts particular emphasis on the development of human resources, with 94% of children receiving a primary education (Japan Committee for UNICEF, 2017). However, a 2018 UNICEF study found that about a quarter of Palestinian boys and about 7% of Palestinian girls drop out of school by the age of fifteen. Problems with the quality of the education, content which is not perceived to be relevant to actual lives, physical and emotional abuse by school staff and fellow pupils, and armed conflict have been cited as the major reasons for this.

Armed conflict creates particular difficulties for education in Palestine. For many children in the West Bank, the journey to and from school requires passage through checkpoints and places where the roads have been blocked off and the avoidance of Israeli settlements. Children are occasionally stopped and questioned on the way to school. In Gaza, according to data for 2013, there are only 645 schools for more than 1.3 million children of school age; 49.1% of the children have double-shift schooling, as opposed to only 0.3% in the West Bank. Although ordinary buildings are being leased and other measures are being taken to address the lack of school facilities and classes, laboratories and other facilities and equipment required by the curricula are inadequate (Human Development Dept., JICA, 2015). In Palestine, children have inadequate access to schools and time for learning. These circumstances mean a range of issues, such as the inability of children to keep up with lessons, a diminished desire to learn, and in particular, violence arising from irrepressible anxiety and fear. Given the marked tendency for children to drop out when they can no longer keep up in class, UNICEF (2018) is seeking safe learning environments where it is possible for Palestinian children to receive a high-quality education.

Palestine 2020: A Learning Nation: Summary of Educational development strategic plan EDSP 2014-2019, published in 2014, commits itself to, sets out strategies and attaches greatest priority to creating education and an environment that is pupil-oriented. It raises ten perspectives that go into the specifics for achieving this. They include the development of curricula, certification of education, and the provision of appropriate and necessary resources for learning (JICA, 2015).

The concern about diversity in education is not limited to Palestine; it is a global trend (Schuelka et al, 2017). Diversity is a multifaceted concept, which the OECD defines as “characteristics that can affect the specific ways in which developmental potential and learning are realised, including cultural, linguistic, ethnic, religious and socio-economic differences” (OECD, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, 2014). The trend is to harness diversity in a positive manner in order to create opportunities for change and development (Kishi, 2019). Palestinian teachers are also striving to provide education, which respects and allows diversity to demonstrate itself in the personalities, strengths, interests, experiences and suchlike of the pupils.

Getting children engaged in class is, more than anything else, is the focus of Palestinian teachers when they want to frame the lesson so that it respects the children’s diversity. This author identified traits in Palestinian education in connection with a Japan International Cooperation (JICA) education project. This involved an analysis of lessons and assistance for intervention in a project for improving the quality of mathematics and science education in Palestine. The author analyzed twenty science lessons that had been filmed in schools in Ramallah, Hebron, Gaza, and Nablus. The analysis found that the lessons do show respect for the diversity of the children. The teachers try to engage the pupils with activities such as skits, games, and experiments; and they provide the children with opportunities to speak in front of class. They also express their praise by clapping hands and so on, when the children have contributed in any way to a lesson.

Visual media has also been harnessed in an enthusiastic manner, given the diversity of knowledge and experiences among the children. It has an important role in places like Palestine, which has issues, such as the paucity of direct experiences among the children, the lack of teaching resources, restrictions on movement, and inadequate learning time. Its use is actively promoted in the Reference Guide/Manual in designing education and active learning: Use of information and communications technologies issued in 2015, which features specific methods and the content that is on offer (State of Palestine, Ministry of Education and Higher Education, 2015).

In considering how to harness visual media for such education, this paper will first of all shed light on the distinguishing features of its use. Next, it will consider the prospects for harnessing such media for bringing about education that respects and enables the demonstration of the diversity of the pupils, in their individual personalities, strengths, interests, experiences, etc.

2. Distinguishing Features of Visual Media Use in Palestinian Education

This paper has relied on the findings of two studies to consider the distinguishing features of lessons that use visual media so that they might respect the diversity of children. The studies were carried out in connection with the JICA project to improve the quality of mathematics and science in Palestinian schools. The first was an analysis of twenty lessons filmed at schools in Nablus in the north, Ramallah in central Palestine, Hebron in the south, and Gaza. The other was direct observations of lessons and interviews with teachers over a total of sixteen days in the periods 27 April-4 May and 8-19 September 2019. May 2019 saw visits to three schools, while eleven were visited in September, with twenty-five lessons being observed overall. The teachers were interviewed on how they were using visual media.

Analysis revealed that the teachers were using visual media for (1) providing indirect experiences: (2) extending themselves; (3) out-of-school activities relying on social media; (4) projectors to get joint attention; and (5) creative dialogic practice. Each of these points will be covered in detail below. The quotes are taken from the interviews with the teachers. The teachers spoke in Arabic.

- 2.1.Providing Indirect Experiences

Audiovisual media, including the visual kind, has been used to provide indirect experiences. An experience is called indirect when the object is encountered indirectly (in substitute form) by images or other means. The children in Palestine do not have sufficient opportunities for directly experiencing objects owing to the restrictions imposed on their movements by political and economic factors. Enabling children to generalize and conceptualize (form concepts from) experiences is an important objective of education (Dale, 1950; Mizukoshi, 1979). Forming concepts, however, is difficult in the absence of underlying experiences.

A teacher made the following comment in an interview:

Images enable us to take in the sea even when we can’t see it. They enable us to find out about snow even if we haven’t seen any.

Palestinian teachers have striven to provide indirect experiences via visual media out of an awareness of the problems children have in understanding school subjects in the paucity of specific experiences.

We see an example in Photograph 1 on the left, which shows a teacher using illustrations in a French lesson. The pupils were learning the words for snowboard, kayak, cycling, horse riding, and sleigh, even though they have no actual experience of those things. This was a comment from the teacher:

Language classes involve learning about a country’s culture, values, and customs through its language, but the pupils will only memorize mere words unless they can form images with them. Today we used illustrations, but we would like to use video media.

We have a similar situation in Photograph 1 on the right, which shows a science lesson. The children are referring to the photographs in the textbook and what is being shown on the whiteboard. The teacher resorted to images to show initially the likes of colors, movements, changes, and structure, because the children would otherwise not be able to get a detailed grasp of the concepts.

It can be argued that visual media is an effective tool for indirect experiences, in that it can make allowances for the differences in direct experiences and knowledge.

Photograph 1: Using media for explaining concepts

- 2.2.Teachers Extending Themselves

The inability to cover the required content within the given lesson times, owing to the sheer scope and volume of the existing curricula, is an issue for education in Palestine. Palestine revised its curricula and textbooks for science and mathematics with Japanese assistance in 2016. A bilateral project was implemented for helping Palestine modify the curricula and texts for those subjects at the elementary level.

JICA has produced an online article about this initiative (JICA, 2018), which informs us:

The textbooks, which been crammed with too much information and rather demanding on children, have been transformed to include experiments and other activities that make them easier to follow and inspire children more to learn for themselves. Experiments and activities are an effective approach for stimulating the desire to learn and boosting comprehension among children. Observations nevertheless found that the experiments and activities, owing to the time it takes to prepare and implement them, do not resolve the fundamental issue of teachers not being able to cover required content within given lesson times.

The issue, in these circumstances, was resolved by teachers harnessing visual media. They used it to explain how an experiment, activity or suchlike would be conducted, and while the children were watching this, the teachers went about preparing the experiment or other task. Photograph 2 shows a science lesson. While the children were being shown images of an experiment, the teacher was writing the key points and process for it on the whiteboard. The teacher made the following comment:

While the pupils were looking at the images, I was writing the main points and process for the experiment on the whiteboard. Once this has been written up, the pupils can refer to whiteboard while the experiment is in progress.

In other words, putting visual media in charge of the explaining gave the teacher leeway to do other things, such as prepare an experiment and check on the pupils’ notes.

Using visual media in this manner can regarded as a physical extension of the teacher. It was McLuhan (1987) who perceived media as an extension of ourselves. McLuhan argues that teachers extend themselves in the act of teaching, in the same manner that wheels are an extension of the legs, clothes an extension of the skin, and cars an extension of the whole body.

With visual media, teachers are augmenting the act of teaching, enabling them to guide and assist pupils in accordance with the actual situation.

Photograph 2: Using visual media and the whiteboard for a science experiment.

- 2.3.Out-of-School Activities Relying on Social Media

There was also a case where social media-based visual media was used. A science teacher at a boys’ school in Ramallah created an online group with his pupils to upload images to help explain experiments. The pupils looked at them before class. The teacher commented:

I get parents to help out in this as not all of the students have a computer or smartphone. I give the illustrations to students beforehand, because not all of them will keep up from just a single glance in class. They can take part in the lesson having looked at them any number of times until they have understood.

Even though the lessons were configured the lesson like a flip class, visual media was used chiefly as an auxiliary resource for the children who could not keep up.

Although this study came across only one example of out-of-school learning involving visual media uploaded on social media, many teachers are interested in this method. When the above case was raised in interviews, teachers expressed much interest in it as a means for resolving differences in aptitude and levels of comprehension. Achieving this would be difficult, however, given the paucity of available visual media.

There are three main sources for the visual media used in Palestinian schools: (1) material supplied by the Ministry of Education; (2) material downloaded from the internet; and (3) material produced by the teachers themselves. The material supplied by the Ministry of Education comes in DVD form, which means it cannot be used at those schools that do not have a DVD player. The visuals that can be obtained from the internet are not always compatible with Palestinian culture, contexts, and textbooks. Visual media is therefore sometimes produced by the teachers with the help of the community, parents, and the pupils.

The scarcity of available media is an issue, even though visual media is effective for children who differ in aptitude and comprehension, helping each of them learn at his or own pace.

- 2.4. Using Projectors to Get Joint Attention

Dealing with the varying aptitude, comprehension, and willingness to learn among the children is a major issue that education in Palestine must resolve. It is extremely difficult for a single teacher teach the same thing, in the same manner, at the same pace for a diverse group of children. Teachers employ various teaching methods to draw children’s attention in the 40-minute lessons. One of them is getting joint attention with a projector, which directs the children’s gaze to the front. Photograph 3 on the left is an example. The teacher is using a projector to enlarge what is appearing in the textbook in order to direct the children’s eyes to the front. This had them looking at the same things and contemplating matters at the same pace. Observations reveal that children soon lose motivation if they cannot keep up. During lessons, teachers were checking that the children were keeping up. Photograph 3 on the right is another example. The teacher was using a projector during an eighth-year science lesson to show illustrations of reptiles, which were projected on to the whiteboard. The teacher had directed the children’s eyes to the front and was also using notes on the whiteboard to give an explanation. Framing a lesson so that as many children as possible can easily follow from the outset is referred to as universal design.

Universal design has all of the children doing the same things in the same manner so that as many of them as possible can keep up with lessons. However, it should be noted that the children who cannot do things in the same manner as everyone else will stick out. Although comprehension, rather than having everyone learn in the same manner is crucial in a lesson, universal design can be called a teaching strategy that shows consideration for the differing comprehension of children.

Photograph 3: Using projectors to get joint attention

- 2.5. Creative Dialogic Practice

Visual media was being used to draw out the children’s knowledge in dialogue form. Let us look at the English lesson in Photograph 4 as an example. The teacher had the pupils watch an American Pink Panther cartoon after listing on the whiteboard the objective of the lesson: the past-tense.

The teacher subsequently asked “What happened to him?”

A pupil replied, “He went to the hospital.”

The teacher went on to ask, “How many times did he go to the hospital?”

Another pupil replied, “He went to the hospital three times.”

The teacher wove the pupils’ replies from their diverse observations into something like a conversation rather than a question and answer session. She moreover added questions along the lines of “Why did he go back home?” and “How did he feel?” in order to get the pupils’ imaginations working.

The teacher wrote up the pupils’ comments on the whiteboard. This record was subsequently used to explain the past tense. Moreover, the new vocab used by the pupils was marked in red for everyone to learn. The lesson went on to learn new English words.

The lesson used a Pink Panther cartoon, which the pupils could easily relate to and enjoy. The pupils learned English expressions, imaging what the Pink Panther character felt and thought. Encounters and linking up with diverse ideas are important for creative dialogic practice. In the example, during the introductory stage of the class, the teacher arranged an encounter in which the children were able to have fun watching a cartoon and think about what would happen to the protagonist, the Pink Panther. It was like the start of a fun game. The comments arising from this game were unforced, impromptu, imaginative, and creative (Holzman, 2014). The teacher produced learning akin to a game from the diverse questions and interest shown by the children. It was improvised, collaborative, and unscripted.

Photograph 4: Creating a conversation from a cartoon watched in class

Palestine, as a region effected by conflict, has to contend with the varying aptitude and the willingness to learn arising from lack of direct experiences and teaching resources, restrictions on movement, and insufficient time for learning Visual media was being used for diverse groups of children (1) to provide indirect experiences; (2) enable teachers to extend themselves; (3) for out-of-school activities relying on social media; (4) with projectors to get the joint attention of the pupils; and (5) for creative dialogic practice.

Palestine is likely to make more progress in the education it seeks – education which is centered on pupils and which respects their diversity.

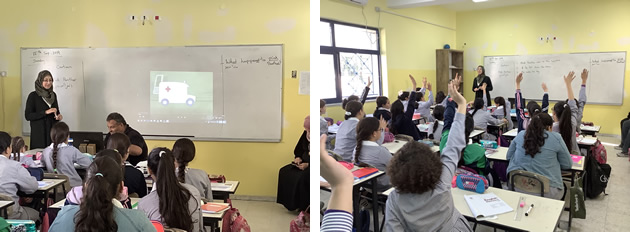

The classroom environments in Palestine are gradually being equipped. (Refer to Photograph 5.) Information and communications technologies are slowly starting to be adopted, and classrooms are likewise being laid out with furnishings and equipment to facilitate group learning. Teachers and textbooks will no longer be the sole sources of information for learning. There will be a range of resources to use and choose from.

Photograph 5: Classroom environments that can handle a range of lesson styles

- 3.1. Wider Range of Lesson Styles

While lessons are being framed to respect diversity, it is not easy for just one teacher to handle the learning for dozens of diverse children. What should be learned and the methods for doing so fundamentally vary according to the individual. Many schools in Palestine, though, follow a standardized pattern, which has everyone doing the same things in the same manner. Children are ranked according to achievement or the lack thereof, which produces dropouts. There have been times when education that has children vying with one another and doing set things according to set patterns was deemed reasonable, but in light of the situation in Palestine, if anything, the capacity for children to learn and create for themselves is required.

Fostering these capacities first of all requires a review of the style of the lessons. A range of styles rather than a standardized approach is required. They include lessons tailored to the individual, where the children can learn separately according to their aptitude and level of comprehension, which we saw in Section 2.3; lessons that follow a collaborative style of the kind we saw in Section 2.5, which has a diverse body of children pooling their abilities to achieve meaningful learning as a collective body; as well as the project approach based on children generating and exploring questions (Tomano, 2019).

The science program Think Like a Crow! supplied by NHK for School in Japan is an example of harnessing visual media for the project approach. The series depicts everyday scenes, such as the airflow inside a train carriage, to get the viewer to ask: what is the science behind this? It provides exploratory learning from children’s inquiries.

A greater range of lesson styles would move children away from one-way learning and assessment to learning and creating for themselves. There are various possible uses for visual media according to the style of lesson.

- 3.2. Drawing on Diversity

Diversity is a resource for producing development-oriented activities in the classroom. Children bring a diversity of discoveries and observations to a lesson. In a science lesson, for example, the teacher can draw on surrounding things or events depicted in images to pose questions to the children outside of the bounds of the textbook, along the lines of “Why do birds fly differently?”, “What makes light reflect?”, “Why are other colors visible?”, “Why does a chair have four legs?”, “Why do fish die out of water?”, and “Why are the school desks this high?

A range of questions is the door to getting children to take an interest in science. Encountering different questions children have not thought about before can encourage a scientific interest in their surroundings and little by little fire their curiosity in science. In a classroom, the teacher is not looking at objects to control, but children with a range of talents and possibilities.

Moreover, while differences in aptitude and the willingness to learn (diversity) are a problem in classes that take the standardized approach, if the diversity is to be harnessed, there is a need to start activities that have everyone teaching and learning from one another. Even wrong answers from children are a resource for development-oriented lessons.

There are at least two criteria for selecting visual media for education that draws on diversity. One is choosing images compatible with Palestinian contexts, which the children can view and interpret in relation to their own experiences and knowledge. The second is the avoidance of too much information. The imagination of the pupils is stunted, and it is difficult to elicit a range of views and ideas from them when they have been shown images with the objective of providing information for them to remember and produce the right answers.

This paper has shed light on the distinguishing features and considered the prospects for education in Palestine that is fostering a pupil-centered approach and that respects diversity. This was done by looking at how visual media is being utilized. Palestine not only has to contend with the political and peculiarities and fragilities of a region affected by conflict; like other countries, has to contend with globalization, growing inequality, child poverty and dizzying changes in education. Education that fosters a pupil-centered approach and that respects diversity will nurture people in Palestine who can think for themselves, continue to learn, and create new things.

The process of getting children to come into contact with a range of ideas, talk with one another, and engender common understanding is indispensable for cultivating the capacity for continued learning and creation. An environment for this kind of education is being put in place in Palestine. We can look forward to the evolution of education fostering a pupil-centered approach and respecting diversity.

To foster such education, debate is also required on the building the professional competence of teachers and assessment. Disconnect with the wishes and wants of children inevitably arise in the process of actually pursuing education that respects their diversity. The key factor at such times is the extent to which teachers are prepared to be on the children’s side and whether the teachers are flexible enough to modify their own ideas (Kobayashi, 2004). Teachers therefore need to look out for and be ready to improvise lessons around the talent and possibilities of the children in front of them (Lobman & Lundquist, 2016). Moreover, methods must also be developed for assessing the diverse performance of children as opposed to the conventional assessment based on what children have memorized. The author will continue to pursue this issue of research with teachers and other people in Palestine.

Bibliography

- Dale, Edgar. Gakushūshidō ni okeru Chōshikakuteki Hōhō (Japanese translation of Audio Visual Methods in Teaching), trans. Shigenori Arimitsu, Seikei Times, 1950.

- Holzman, Lois. Asobu Vigotsukii: Seisei no Shinrikgaku e (Japanese translation of Vygotsky at Work and Play), trans. Yūji Moro, Shinyosha, 2015.

- Japan Committee for UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2017: Children in a Digital World, 2017, 2017, Table 5 Education, p. 170.

https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/SOWC_2017_ENG_WEB.pdf - Japan International Cooperation Agency. Kyōiku wa Akurui Mirai wo Hiraku: Paresuchina de 20 nenburi no Kyōkasho-kaitei wo shien (Education opens the way to a bright future: Assisting Palestine in the first revision of its textbooks in twenty years), 2018.

- —–, Human Development Department. Paresuchina Jichiseifu Kyōiku Sekutā Kisojōhō Shūshū-Kakunin Chōsa Hōkokusho (Report on survey to gather basic information and ascertain the education sector in the Palestinian National Authority), 2015.

http://open_jicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12268884.pdf - Kishi, Makiko. 9 Shō, Ibunka Rikai to Kōkan (Chapter 9: Understanding and exchanges with different cultures) in Shūta Kagawa, Norifumi Arimoto, Yūji Moro, eds. Pafōmansu Shinrigaku Nyūmon: Kyōsei to Hattatsu no Āto (An introduction to performance psychology: The art of inclusiveness and development), Shinyosha, 2019. pp. 121-136.

- Kobayashi, Hiromi. Shidō Keikaku no Ritsuan wa zero jian kara, Kodomo no Negai wo Ukeiretsutsu, n Jian e to Shūsei wo Kasaneru (Coming up with guidance plans: Modifying from plan 0 to plan n, incorporating children’s wishes) in Sōgō Kyōikugijutsu (General education technologies), Shogakukan, May 2004 edit. pp. 32-34.

- Lobman, Carrie & Lundquist, Mathew. Inpuro wo Subete no Kyōshitsu e: Manabi wo Kakushin suru Sokkyō Gēmu Gaido (Japanese translation of Unscripted Learning: Using Improv Activities Across the k-8 Curriculum), Shinyosha, 2016.

- McLuhan, Marshall J. Mediaron: Ningen no Kakuchō no Shosō (Japanese translation of Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man), trans. Yutaka Kurihara & Nakakiyo Kawamoto, Misuzu Shobo, 1987.

- Ministry of Education and Higher Education, State of Palestine. Palestine 2020: A Learning Nation: Summary of Educational development strategic plan EDSP 2014-2019, 2014.

- —–. The Reference Guide/Manual in designing education and active learning: Use of information and communications technologies, 2015.

- Mizukoshi, Toshiyuki. Jugyō Kaizen no Shiten to Hōhō, (Perspectives and methods for improving lessons), Meijitoshoshuppan, 1979.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. Tayōsei wo Hiraku Kyōshi Kyōiku: Tabunka Jidai no Kakkoku no Torikumi (Japanese translation of Educating Teachers for Diversity: Meeting the Challenge), trans. Satomi Saitō, Ayumi Fukawa, et al. Akashi Shoten, 2014.

- Schuelka, Matthew J., Johnstone, Christopher J., Thomas, Gary, Artiles, Alfredo J. The SAGE Handbook of Inclusion and Diversity in Education, SAGE Publications, 2017.

- Tomano, Ittoku. Gakkō wo Tsukurinaosu (Rebuilding schools), Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2019.

https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/2576/file/SoP-OOSCIReport-July2018-AR.pdf.pdf - UNICEF. State of Palestine: Country Report on Out-of-School Children. 2018.

https://www.unicef.org/mena/sites/unicef.org.mena/files/2018-07/OOS C_SoP_Full 20Report_EN_2.pdf

Makiko KISHI

Meiji University

Associate Professor, School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University.

Field of expertise: educational technology. Pursues research on education and learning environments for diversity. Has focused on the comprehensive learning periods and other exploratory learning in Japanese schools. Outside of Japan, has focused on the Middle East (Syria, Palestine, Turkey), studying the design and pursuit of places where anyone, including the children of refugees and other socially disadvantaged children, can display and mutually develop their diversity, in terms of their personalities, experiences, strengths, and so on.

Return to 28th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 28th JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page