22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium

March to December, 2014

The Internet and TV Stations in the Asia-Pacific Region

[Discussant 2] Television program distribution in the Internet age

The theme for this year’s symposium—The Internet and TV Stations in the Asia-Pacific Region—has its origins in an issue with which JAMCO has been contending in recent years. One of JAMCO’s key missions in its works in the public interest is to provide outstanding television programs that have been produced in Japan to TV stations in developing countries free of charge. The contract that JAMCO draws up for the provision of such programs includes a clause that prohibits the distribution of the programs via the Internet. There have been cases to date in which although the station that is to receive the programs is appreciative of the purposes of JAMCO’s activities and full of praise for the broadcasting contents, the Internet prohibition clause presents a sticking point that forces contractual negotiations to be broken off.

For the provider the tendency is to believe that there should be no reason for the online distribution restriction to obstruct a contract for broadcast programs. However, for the counterpart country the mindset seems to be that this restriction could result in it not being able to fulfill its contractual obligations, or that without the option of online distribution the free provision of programs loses its attractiveness.

Given that the JAMCO Online International Symposium is one of the major annual events in our calendar each year, we were hesitant about setting a theme that dealt with an issue that is so close to home. However, when we took a look at the reality of the situation—and this was the "reality" at the time we were selecting the theme for the symposium—it was evident that on a commercial basis although Korean contents are being broadly distributed throughout the Asian region, exports of Japanese contents are lagging behind. Why are Japanese contents not permeating the market, and does the option of online distribution, or lack thereof, have an impact on acceptance of contents? We determined that in order to shed light on such questions it would be beneficial to hold the symposium not simply from the perspective of JAMCO’s activities, but rather as a means of sharing information on this topic among various countries. This was the starting concept for this year’s symposium.

Six months have now passed since the formation of this initial concept. For the organizers the contents of the country reports we have received have been unexpected in the following two senses. Firstly, the reports do not cover in great detail some of the things we sought to find out, namely the status of domestic distribution and broadcasting of overseas contents, the proportion of overseas-produced programs that are purchased or leased, and the degree to which these contents are distributed online. This is of course no reflection on the authors who were selected. It is rather the case that there is a vast, unquantifiable volume of contents that are distributed through multiple windows on a daily basis. This is the second point that was contrary to our expectations.

The reality of TV everywhere

At the very most it is only at the point when programs are broadcast over the airwaves by terrestrial broadcasting stations that the origins of broadcasting contents are checked in any great detail, including such matters as country of origin, copyright, and replays. Simultaneously with the terrestrial broadcast, or some time thereafter, the contents then make their way online. This Internet-based transmission may be a legitimate business or non-profit activity by the broadcasting station or related body, but it may also be a legitimate or non-legitimate business or non-profit activities by another party. Broadcasting contents with no defined origins are transmitted through the same channels. This is the situation as currently experienced by contents providers, making it virtually impossible to quantify with any certainty the number of programs being broadcast and their ratings.

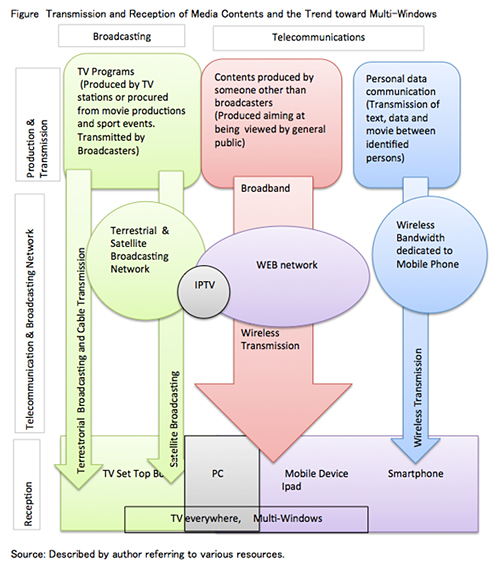

The figure below attempts to visualize the complex situation for broadcasting contents, with the contents producers and transmitters positioned at the top and the audiences who receive the contents at the bottom. From the viewer’s perspective this means nothing more than watching what they want to watch when they want to watch it on a medium that is close to hand at the time. This seems to epitomize the concept of "TV everywhere," but the viewers no longer concern themselves whether what they are watching is actually "TV" or not. Just as there will be people viewing contents via cable or airwaves on a large-screen TV set, there will also be people viewing the same contents via wireless communications on a smartphone or tablet. The preference of the younger generation is shifting to mobile terminals, and with this shift comes a tendency to watch contents designed to be viewed in a short timeframe. Both broadcast and non-broadcast contents are flowing into web networks through various channels, from where they then flow out once again.

The scenario set out above could be seen as a premonitory vision for Japan in the near future. This may well be the case for the Japan, but it is already a reality in the countries of Asia, at the very least Malaysia, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Korea.

A number of issues raised in the country reports that support the observations made here are selected and examined point by point.*1

Viewers’mobile shift

Firstly, from the country reports*2 we can confirm the current situation of a viewer shift away from television sets to an online environment. In Thailand, most people use one of four media platforms—television, personal computers, smartphones and tablets—but approximately 49 percent of time spent connected to media is via smartphones. It is predicted that at some point in 2014 viewing times via the Internet will surpass television viewing times for the first time. In Sri Lanka Internet TV is cheaper than cable because users only have to pay for the connection charges, meaning that television viewing via the Internet is on the rise. This illustrates clearly that viewers are watching television programs and other contents on computers and mobile terminals.

As illustrated at the bottom of the figure, viewers who receive contents have multiple windows to choose from. So what is it that people are going online to watch? In the country reports there were three very interesting statements. Firstly, in the case of Thailand, the time people spend watching television programs on mobile terminals is increasing. Other uses for mobile terminals other than viewing televisions programs are cited as being largely e-mail for adults and online games for younger people. In contrast to a conventional television set, which can only be used to watch television broadcasts, the advantages of other devices are becoming readily apparent, in that they can be used for multiple purposes, including viewing television programs.

In Thailand it was found that 24 percent of Internet users access content through computers using fixed or wired connections, whereas those who connect wirelessly via smartphones or tablets account for 32 percent of users. As both Korea and Malaysia have well-developed fiber optic networks there was no overt inclination towards mobile access observed.

The trend away from television sets and shift to mobile technologies is particularly notable in the younger generation. It is noted that in Korea there are dramatic changes taking place in viewing formats and in Malaysia it is considered important to grasp the attention of the young by diversifying transmission methods, which has led to portal web television stations gaining the most attention. The situation is similar in Thailand, where the broadcasting industry has put together packages that are aimed particularly at younger age groups.

Broadcasters’online shift

This raises the question of how broadcasting stations are responding to the changes in media choice, particularly among the young. The broadcasting stations of all countries are strengthening their online distribution and contents. One of the quickest countries in the world to take action in this regard was Korea. Since 1999 the three terrestrial broadcasting stations have launched web-based services one after the other. In addition to the fact that the broadband network was already well-established in Korea at the time, as copyright belonged to the stations themselves they executed a shift to online contents ahead of any other developed nation. Real-time broadcasts and pay-per-view catch-up services are also being provided.

In the case of Malaysia it is noted that 2012 was the year in which television really took off from its terrestrial-based roots. Since 2009 Malaysia’s public broadcaster RTM has offered a VOD service known as Myklik, which lets viewers watch programs on demand after their broadcast dates. This service was supplemented by Mystream, a live streaming service, in 2012, and RTM Mobile was launched in 2013 as a mobile app offering live streaming. In the case of Sri Lanka, it is reported that there are 44 registered television channels, including satellite and cable, although most of these channels provide their programming via the Internet. In Thailand too, broadcasting stations have developed their own "new media" channels.

The bright and dark sides to online broadcasting

Although moving away from their dependence solely on the broadcasting frequencies they possess and taking the plunge into the online world of the Internet can lead to new business opportunities for broadcasting stations, it is nonetheless an agonizing choice to delve into this intensely competitive sphere. For those who choose to take this path there is the prospect of being able to expand audience demographics, including the young and overseas diaspora. The converse side is the concerns that arise for commercial broadcasters about the potential for a loss of revenue, that programs produced by the broadcaster will be duplicated and utilized without limitation, giving rise to further concerns about the legal issue of copyright infringement.

In the country report from Sri Lanka there is an illuminating account of the bright side of online broadcasting, namely expanding viewer numbers. It is reported that approximately three million Sri Lankans live abroad, equivalent to one-seventh of the total population, including two million people who constitute the diaspora in Europe, a great many of whom wish to watch Sri Lankan television via the Internet from abroad. In the case of Malaysia too it is noted that 6 percent of downloads from the abovementioned RTM Mobile are made from Singapore. Korea reports on a service for receiving Korean programs in the United States. These kinds of Internet-based broadcasting have the power to draw in not only the young who have moved away television sets, but also to attract overseas viewers.

On the other hand, a case from the Korean report amply illustrates the dark side of online broadcasting, noting that when a payable view site was launched there was an inevitable spread of illegal distribution channels. In Korea terrestrial television programs are being distributed illegally through the offline proliferation of Internet protocol television (IPTV) contents. People who have used these illegal distribution services are said to account for more than 20 percent of the total audience.

Not only does illegal distribution make a mockery of the Internet business models of broadcasting stations, it also causes copyright infringement. The Korean report details an ironic example of how an illegal television viewing service was provided for Koreans living in the United States, but as the service was payable the viewers did not realize that it was illegal. In the case of Thailand it is noted that while the major commercial or publicly owned stations have to confirm to the full range of commercial and copyright regulations, the small private or independent Internet TV stations do not, putting the major stations at a disadvantage in Internet-based business, both competitively and legally.

Distribution of overseas-produced contents

Korea is well-known as the leader in Asia for program exports, particularly dramas. However, in 2011, 49 percent of total exports of US$190 million (2011) were to Japan, demonstrating that revenue sources are skewed towards Japan. Korea is now aiming to expand Internet distribution in China and utilize platforms that target Southeast Asia.

In Sri Lanka television dramas produced in Japan, Korea, China and India are all broadcast, with Indian dramas in particular gaining acceptance in recent years. In Thailand sources of overseas programs are cited as being China, Hong Kong, Korea and Japan. Malaysia reports that overseas contents account for 20 percent of contents overall. This is a measure that has likely been stipulated to create a ceiling for overseas contents, from the perspective of protecting local contents. It is similar to the case in Sri Lanka where a law requires broadcasters to pay a charge similar to an import tariff when broadcasting overseas programs.

Issues for the future

Assuming that the online shift among viewers is only going to progress further, an issue for broadcasting stations is likely to be the development of contents tailored to online viewing. For countries and telecommunications operators the challenge will be to expand and enhance wired and wireless broadband networks that will support the transmission and reception of online video contents.

Sri Lanka raises the issue of maintaining archives as a challenge relating to contents. This is a unique and important perspective that was not touched upon in other reports. However, given the costs and the need to ensure a power source it is unlikely that viewers would be use mobile terminals to view a one-hour drama or similar program, neither is it desirable from the perspective of the use of limited bandwidth and transmission waves. Mobile terminals are therefore likely to create their own demand for mobile-oriented contents.

On this point the Thailand report proposes an alternative viewing structure that allows the busy modern generation to acquire information in a short timeframe and also have access to more detailed information on-demand if required. This is a structure probably created with news and information-related contents in mind. From the Malaysia and Pacific Island nations report we can also infer that in addition to news, sports also have a big draw factor in terms of content. As news loses its value over time and sports rapidly lose their appeal once a match is over, these two are suited to the acquisition of information in real time. Furthermore, unlike dramas, the nature of news and sports make them less likely to be illegally reproduced, thus reducing the likelihood of copyright issues. From this perspective too, they can therefore be said to be contents that are suited to online distribution.

In terms of telecommunications infrastructure, in Korea and Malaysia the presence of a well-established fiber optic network makes program transmission possible through wired networks, such as IPTV. However, given the multiple contents that are available easily and cheaply online, be they legal or illegal, it does not seem that robust infrastructure alone is a sufficient factor to promote IPTV. In Thailand it is noted that the further development of a wired Internet infrastructure and decreases in tariffs will be necessary to promote IPTV further. In the case of the Pacific Island nations it is noted that there is still no broadband network—either wired or wireless—with sufficient capacity to support transmission and reception of moving images.

This paper has identified and reframed a number of issues that were raised in the country reports of Korea, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Thailand and the Pacific Island nations, concerning the current status and challenges for television program distribution in the Internet age. Japanese readers of this online symposium may note that in comparison to these countries Japanese broadcasters have been slow to enter the world of Internet programming and broadcasting. This could be perceived as both failure on the part of broadcasting stations to keep pace with the changing times, and also as reluctance to embark on such measures out of concerns for the gradual erosion and destruction of copyright frameworks. Both the bright and dark sides of Internet broadcasting in Asia will require further attention into the future.

- The various country report statements were taken from papers written in Japanese (Korea and the Pacific Island nations) and in English (Thailand, Malaysia and Sri Lanka), and have subsequently been transposed into Japanese in this paper (of which this is an English translation). Therefore the author adds the disclaimer that words and phrases may not necessarily be the same as those featured in the original country reports. *1

- In this paper, when quoting from the country reports, the country name is used. Although in conventional style it would be normal to cite the author’s name, country names are used in this case for ease of understanding. Sources of citations are detailed below:

Thailand: Sasiphan Bilmanoch, "The utilization of the Internet by TV Stations in Thailand," 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium, March 2014.

Malaysia: Hazizul Jaya Ab Rahim, Abdul Manap Abdul Hamid, "Challenges and Approach Towards IP-based and User-generated Content in Malaysia," 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium, March 2014.

Sri Lanka: Mohamed Shareef Asees, "Internet Usage Among TV Stations: A Case Study of Independent Television Network (ITN) in Sri Lanka," 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium, March 2014.

Pacific Island nations: Kader Hiroshi Pramanik, "Internet Broadcast Status in the Pacific Island Nations, 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium, March 2014. *2

Haruko Yamashita

Professor, Faculty of Economics, Daito Bunka University

Born in Japan in 1957, she obtained Bachelor's degree in Economics from Doshisha University, Master's degree in Economics from the University of Chicago and Doctoral degree from Hiroshima University. Her academic career started in 1995 as an Assistant Professor (and later Professor) of Meikai University. She assumed her current position in April 2013.

Focusing on the studies of the broadcasting and fishery industries, she recently contributed a chapter "International Relations in Asia-Pacific Waters: Fishery as a Main Industry" to Minoru Sugaya (ed.) Telecommunication Policy and International Cooperation in Asia Pacific Region, Keio University Press, 2013.

Return to 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page

Return to 22nd JAMCO Online International Symposium contents page